The Basic Taste Revival

In the aftermath of fashion’s hyper-referential years—defined by the dominance of archival aesthetics and the curatorial impulse of platforms like Instagram—a quieter, more subdued sensibility has emerged. Although difficult to pinpoint, this shift is evident in the resurgence of plain white tank tops, worn-in slub denim, simple T-shirts, and a style that prioritises comfort over performance. It’s an aesthetic that resists fashion’s recent over-intellectualisation. It is not quite normcore, minimalist, or anti-fashion in the traditional sense. As Dazed has aptly put it, it is a revival of basicness.

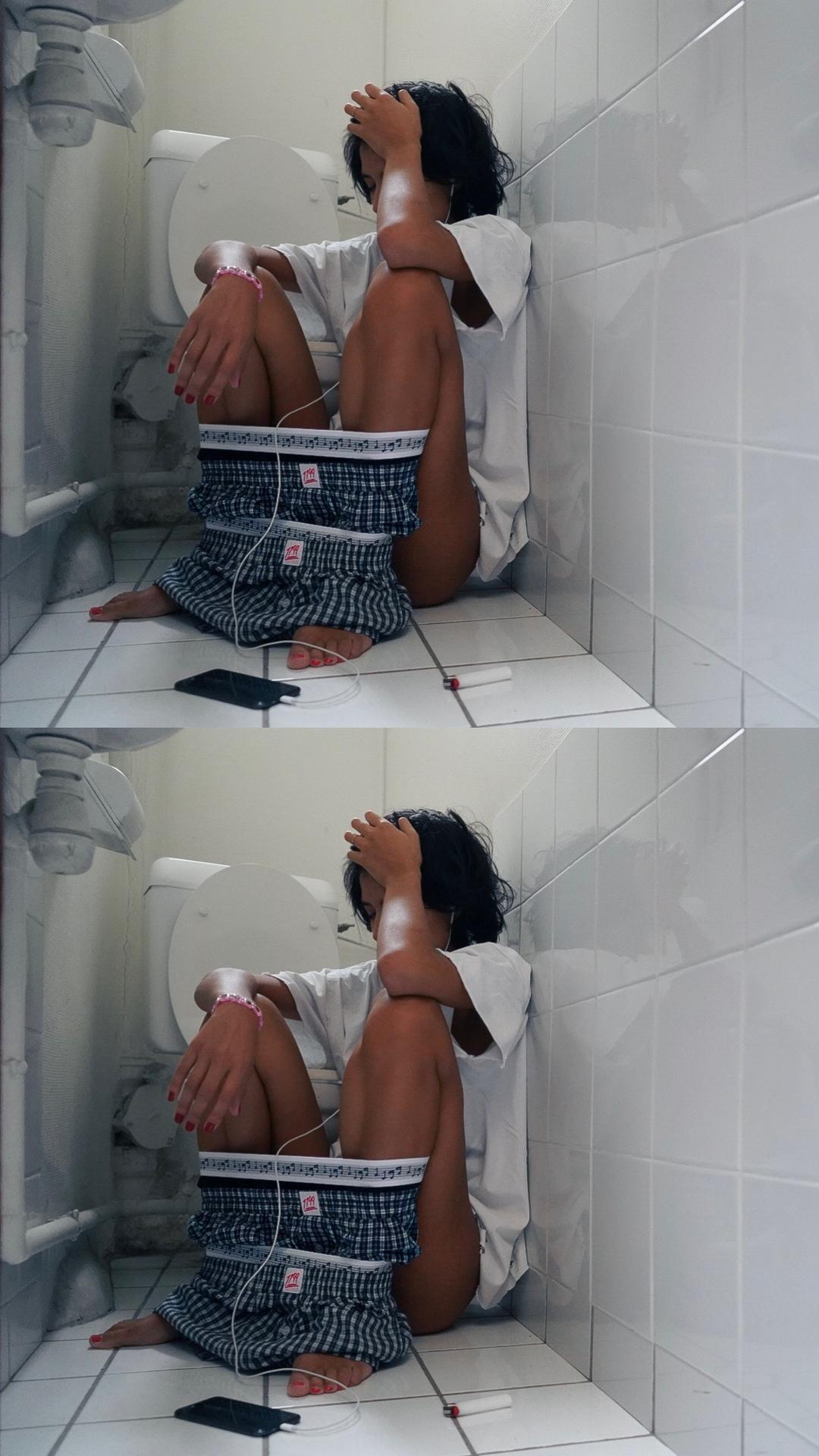

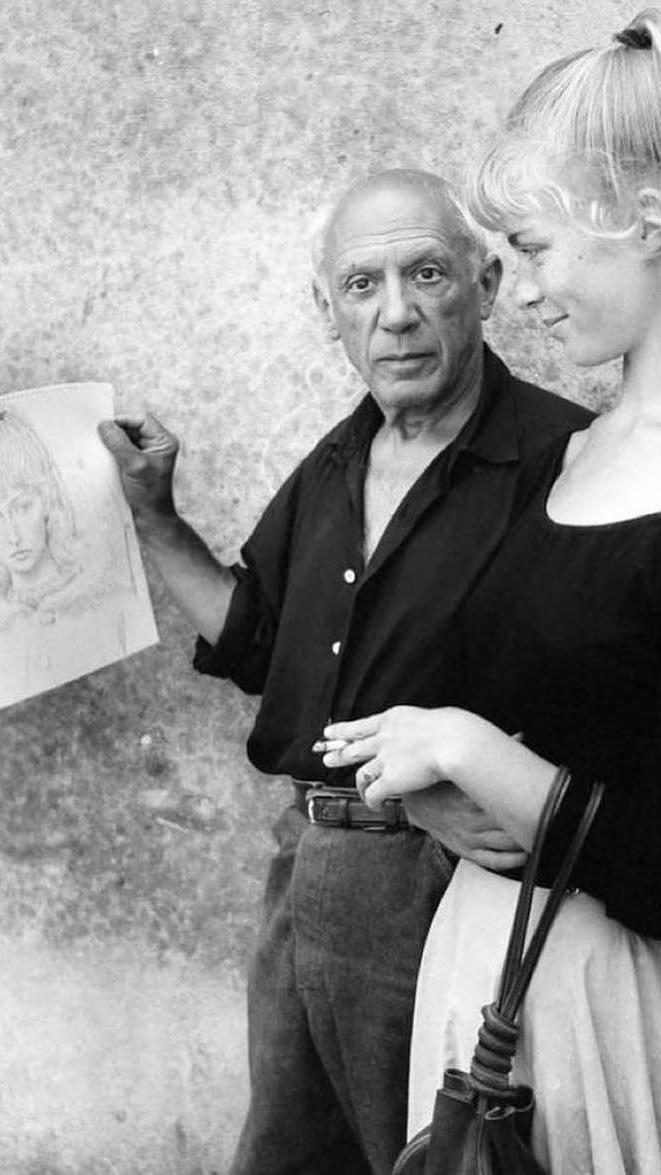

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/bf17985c7331666bd971e27beb657020b65d1fd8-1140x1425.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=570)

Photo by Dina Litovsky

The hyper-referentiality that basicness responds to was evident not only in the resurgence of archive clothing on red carpets—such as Law Roach dressing Zendaya in vintage looks for the Dune press tour, or Bella Hadid in Galliano’s Fall/Winter 1997 collection—but also in contemporary design. Glenn Martens revisited Jean Paul Gaultier’s 1990s trompe l’oeil body prints at Y/Project, while Maria Grazia Chiuri reinterpreted Dior’s mid-century silhouettes for a new generation.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/6d4cfeb08667788cdeedd9750870a28822a578f3-1036x1500.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=518)

Zendaya attends the London premiere of 'Dune: Part Two'.Photo by Samir Hussein

Celebrity street style wasn’t immune to archive fever: Iris Law’s appearance in a vintage Jean Paul Gaultier cardigan prompted media speculation about how celebrity status grants access to coveted archival pieces, and by extension, participation in the broader archival trend. Bella Hadid, too, became a visible follower of this trend; her carefully documented vintage looks, including pieces from Roberto Cavalli and Jean Paul Gaultier, illustrated how even celebrities sought to participate in the revival—where garments often took precedence over the wearer. Clothing became indexical—a marker of the wearer’s fluency, revealing their familiarity with fashion history and discourse.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/d12113de6263be506cd07a75f9574b5267a6b782-1768x2652.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=884)

Photo by Marc Piasecki

To understand how this sensibility took shape, it’s necessary to revisit the digital conditions that preceded it. Although resale sites like Grailed and Depop contributed to fashion’s shifting visual codes, it was Instagram that institutionalised the culture of citation that archival fashion embodied. Instagram encouraged clothing to be photographed and displayed like museum artefacts, creating a style rooted in designer pieces from past collections, less garments than citations, not merely worn but also decoded, catalogued, and displayed.

In September 2023, as the archive fashion era began to lose steam, writer and podcaster Chris Black published a GQ article exploring how Instagram had undermined personal style. “We are now focused on ‘pieces’—buying the one, often high-dollar item—that will make us feel good and give us the instant gratification we need,” he wrote. This “piece” fetishism encapsulates the archive mindset.

Archival fashion prized the historical or aesthetic significance of garments over their practical function. A Raf Simons parka or a Helmut Lang bomber was not just worn—it was referenced. These items circulated as museum objects: photographed against white backgrounds, annotated with season and context and the occasional condition notes, but stripped of lived experience.

To wear Helmut Lang FW98 or Prada SS07 was not simply a stylistic choice—it was an assertion of cultural literacy. This era encouraged a curatorial sensibility, treating garments as historical documents. The body became secondary—a hanger for signifiers. Meaning resided not in how clothes were worn but in their provenance. Style became referential, academic, even disembodied.

Helmut Lang Fall-Winter 98'

The appeal of this system lay in its promise of distinction: it signalled intelligence and aesthetic fluency, particularly in a culture increasingly wary of surface-level taste. Although archive fashion intellectualised personal style, it also alienated it. The rise of fashion Substacks, commentary accounts, and academic-adjacent essays turned style into scholarship. Clothing became a vessel for self-taught expertise.

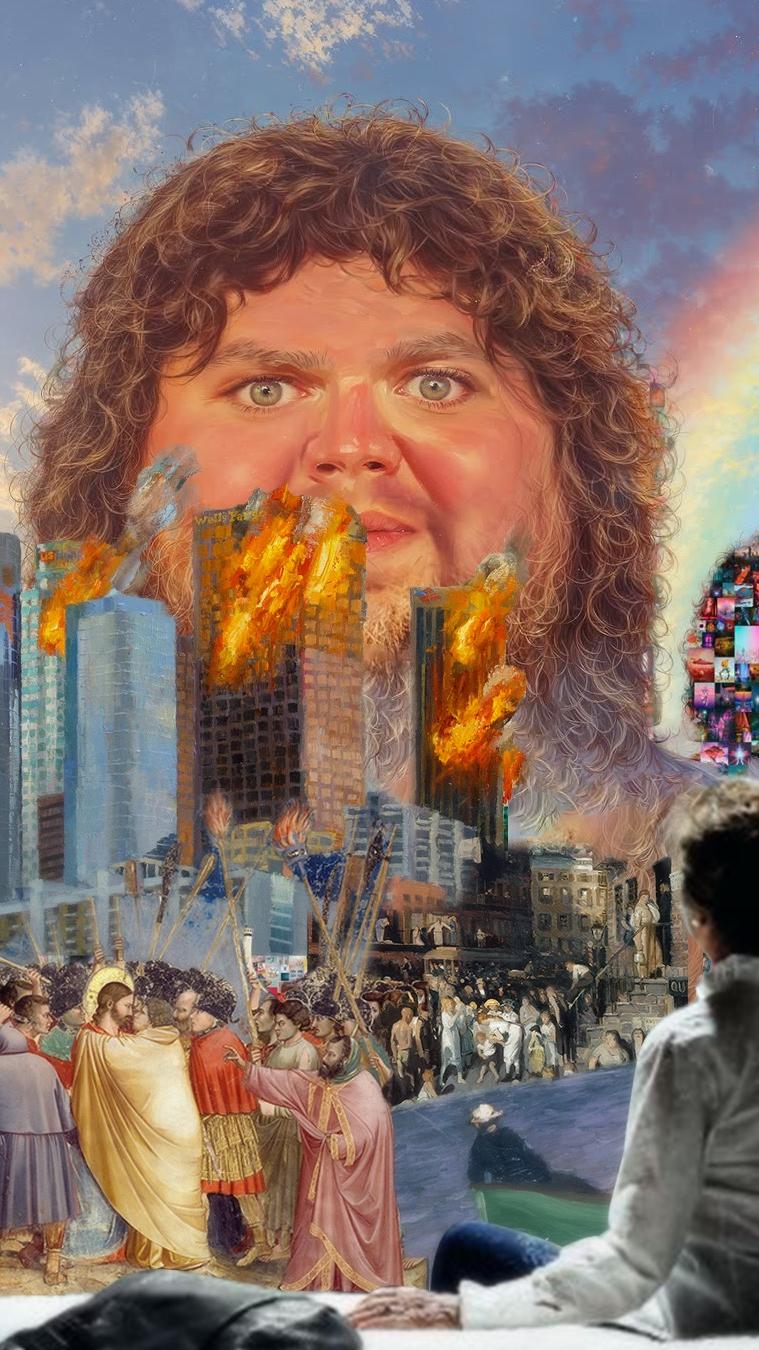

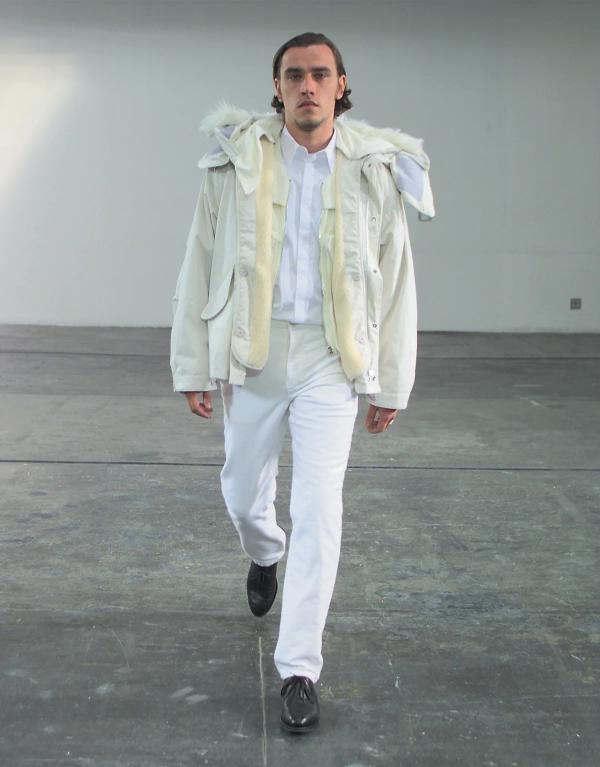

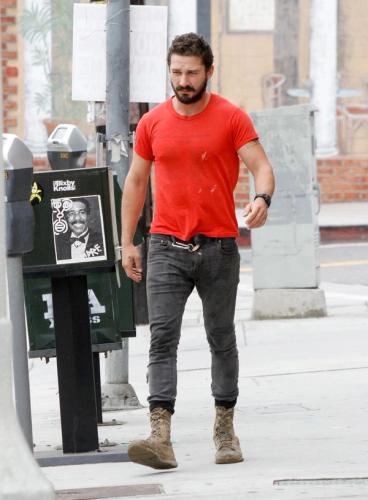

Some of Shia LaBeouf's outfits

As a result, the idea of personal style became increasingly self-conscious and complex. YouTuber and fashion historian Mina Le dubbed it the “personal style epidemic”—a paradox in which individuality became algorithmic. The more users tried to differentiate themselves, the more they gravitated toward the same vintage Raf Simons bombers or Margiela Tabi boots. Identity collapsed into taste; taste into taxonomy. This aesthetic fatigue created space for a shift—a slow disengagement from the performance of uniqueness.

Basicness rejects the recent over-intellectualisation of fashion, opting out of the aesthetic semiotics that defined the archive era. Where archive fashion positioned personal style as thesis, basicness offers a blank page—uncited, uninterpreted, and deliberately mute. Product designer and blogger Lola Dement Myers tweeted:

“I have dedicated my life to understanding counterculture and now all I want to do is wear Brandy Melville short shorts and Uggs.”

This sensibility is better understood not as an aesthetic category but as an attitude. It is a deliberate disengagement from the semiotic arms race of the archive moment. It’s wearing a white tank top without referencing Calvin Klein; worn-in slub denim that signals no era or designer. Though in a somewhat ironic way, it is still about enjoying Lululemon, Brandy Melville, and Uggs for what they are. Fashion commentator Rian Phin once observed:

“Smart art people dress and make their art in a way that seems so obviously unappealing that

it ends up being genius because they’re on the cutting edge.”

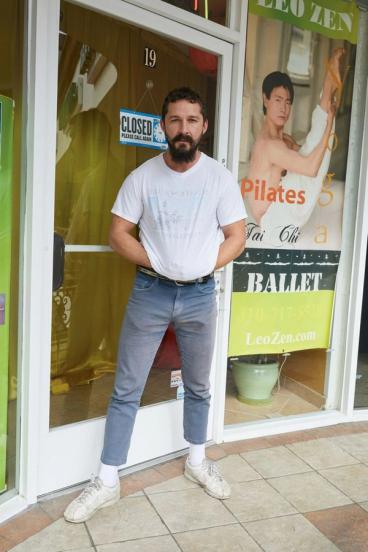

Basicness emerges not as a demonstrative lack of taste but as a new language of fashion. It is anti-propositional: it does not seek to “say” anything and can be read as a response to the collapse of fashion’s internal hierarchy of signs. Basicness asks the wearer to engage with the quieter signals of middlebrow taste, rather than the explicit cultural capital tied to conceptual anti-fashion designers celebrated during the archive era. This sensibility is reflected in the work of designer Raimundo Langlois, who, in an interview with AnOther, describes his style as “...the comfort of always being the same. I’m similar now – only with jeans and a sweater.” His collections, characterized by unbranded tank tops, polos, and jeans, embody a return to understated, high-quality basics.

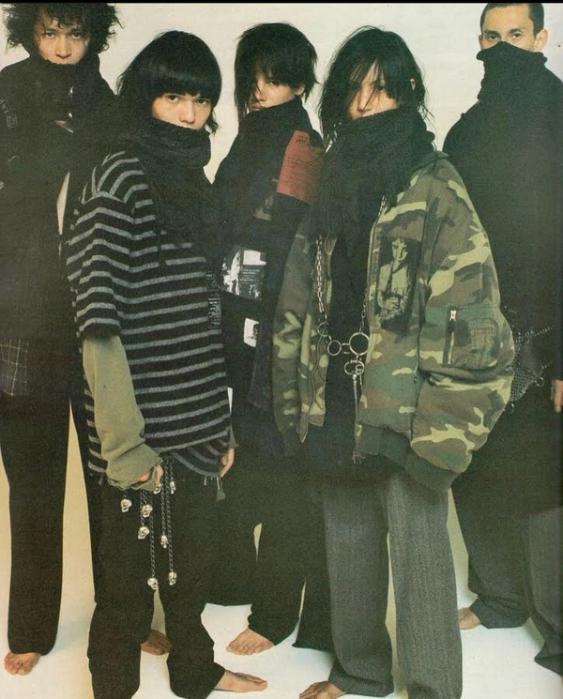

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/2d98c9da46b4778a4c2254b2d6ec876f92dfdfbb-1536x2048.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=768)

Photo by FX

Though often read as a return normcore, basicness is not the same. Normcore was ironic; it treated banality as a costume. Basicness, while not necessarily unironic, is unstudied. It’s not interested in critique or inversion. It’s closer to what Roland Barthes called the “degree zero” of style—a neutral mode stripped of rhetorical flair. If archive fashion spoke in a detached vocal fry, basicness sounds distinctively soft-spoken and earnest. In a time when everyone is expected to brand themselves, basicness offers semantic privacy.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/3d0102b582face99df71378bc8dab00c1166ab27-992x1240.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=496)

Jamie Dornan and Keira Knightley during the 2000s.

Rather than an ironic embrace of banality, basicness can be understood as a reclamation of styles that women were often ridiculed for in the 2010s, interwoven with the influence of 1990s minimalism and the contemporary #CleanGirl aesthetic. This shift toward more pared-back forms of beauty can at times evoke a vision of womanhood rooted in modesty, domesticity, and quiet wealth. Basicness, then, walks a fine line: it can function as a playful reclamation of once-ridiculed choices, but it also risks proximity to more prescriptive—and regressive—codes of appearance.

Another reason for basicness’s appeal is the pejorative weight the term still carries. In recent years, we’ve seen increased cultural disdain for the middlebrow. Women, in particular, have long been derided for embracing styles deemed too popular to be cool: athleisure from Alo or Lululemon, the going-out outfit of black tank tops and jeans, Brandy Melville-core, even Uggs. Basicness is fascinating because it confronts the skill required to artfully pull it off, to make these things “cool.” Some brands have begun to codify this appeal: Tank Air, for instance, has cultivated a cult following around minimal basics like square-neck tanks and halters—garments that appear effortless but rely on precise styling to resonate.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/0d24b2bf5105cb4f35ef33ffe8adcdde47ec334a-602x1050.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=301)

Megan Fox as Jennifer Check, behind the scenes of Jennifer’s Body (2009)

This return to sartorial neutrality follows years of aggressive self-branding. As social media rewarded coherence and legibility, fashion lost spontaneity. Getting dressed became about being “on brand.” Basicness recalibrates what self-expression can look like. If the archive era turned the wardrobe into a library, basicness restores it as a closet. Basic outfits are often photographed on bodies, not as individual garments, flat-layed, and archived. This ties into broader industry trends, including the return of the “uniform”—a preference for clothing that reflects lifestyle rather than signals ideology.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/bb14f95b6de4a3bbeb9ea7925d440d5b5016541f-1312x2000.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=656)

Phoebe Philo during her time as Creative Director of Chloé.Photo by Shoot Digital.

Basicness is not meaningless—it simply declines to convey meaning. It is closer to silence than emptiness. Barthes’s notion of the neutre—a refusal of binaries, a suspension of meaning—feels apt. Basicness resists being decoded by placing itself in the middlebrow, in the masses, in the untheorized.

There is quiet politics in this refusal. In a culture that demands constant articulation of politics, preferences, and personality, opting out can be radical.

The Row Auttumn/Winter Collection (2017)

As fashion’s internal hierarchies collapse and style blurs with branding, perhaps the most subversive gesture is to do less. When everything is curated, authenticity feels like an algorithmic glitch. Basicness welcomes that glitch. It doesn’t promise transformation, transcendence, or even taste: it just promises clothes.