Eras In Film: New Hollywood

In the late 1960s, something changed in American cinema. The polished films of the previous decades started to feel out of touch. Audiences, mostly younger ones, were not interested in neatly packaged stories with predictable heroes. Instead, they were drawn to films that felt real, personal, and sometimes a little uncomfortable. What emerged was a wave of bold, director-driven cinema that we now refer to as New Hollywood. This movement, which lasted from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, marked a period of experimentation and artistic freedom rarely seen in Hollywood before or since, one that has left a lasting mark on the way films are made and understood today.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/c7149cf73decbadd78fd8efa42e67db231b01c9a-2000x1361.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1000)

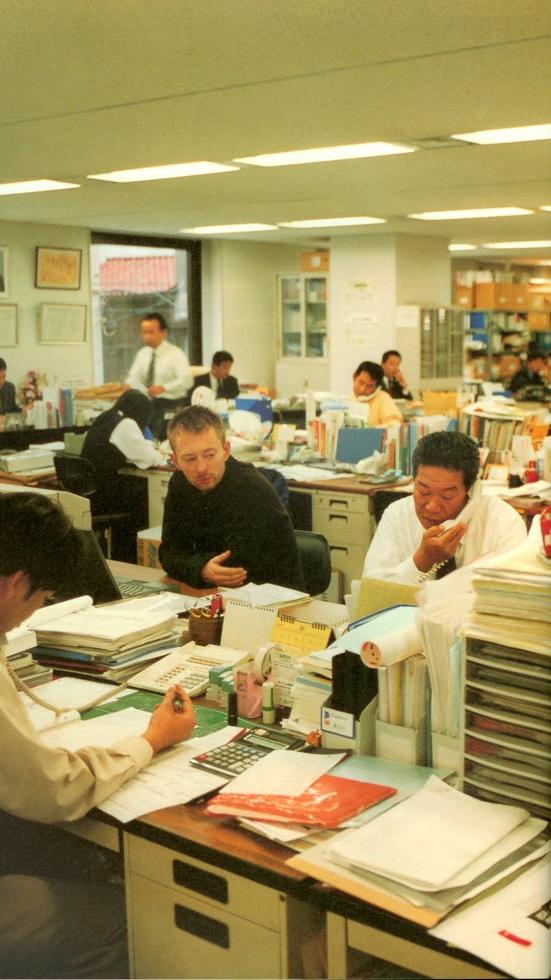

Stanley Kubrick, behind the camera, for the final sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey. From Collection Christophel.

Origins

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/697ee999a1417e55635f0a6aef7f2e509c05cea4-2954x1662.png?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1477)

Still from 'Casablanca' (1942). Courtesy of Warner Bros.

By the 1960s, the old Hollywood studio system was falling apart. Major studios, which once held total control over production, distribution, and even the stars themselves, were losing their influence. Gone were the days of Citizen Kane (1941), Casablanca (1942) and Hitchcock; Television was ascending. Shows like Gunsmoke (1955), Star Trek (1966) and The Andy Griffith Show (1960) pulled in huge viewership with easily digestible, serialised dramas or comedies that people could tune into from home every week. Box office numbers were shrinking. At the same time, the strict censorship rules of the Production Code were replaced by the MPAA rating system, which allowed filmmakers to include more explicit content in their stories.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b743982a6f1a6bb192801b2921b8544a638e803e-1507x1911.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=754)

Publicity photo featuring Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk from Star Trek, released 1968 by NBC

Meanwhile, the country was experiencing serious cultural and political upheaval. The Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Watergate scandal had shaken the public’s trust in authority. Many people, especially young adults, felt disillusioned with American institutions. As a result, there was a growing demand for films that reflected these complex emotions and didn't shy away from difficult subjects. The conditions were right for a new kind of filmmaking to emerge.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/120cbe7921a4044a3432b3294f7f0d9b8001ca4e-2048x1336.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1024)

Still from Michael Wadleigh's 'Woodstock' (1970). Courtesy of Warner Bros.

The DNA of New Hollywood: Style, Themes, and Stars

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f08dbfb24a42c72b0d409235f7d6ad690c97e4d1-1537x1202.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=769)

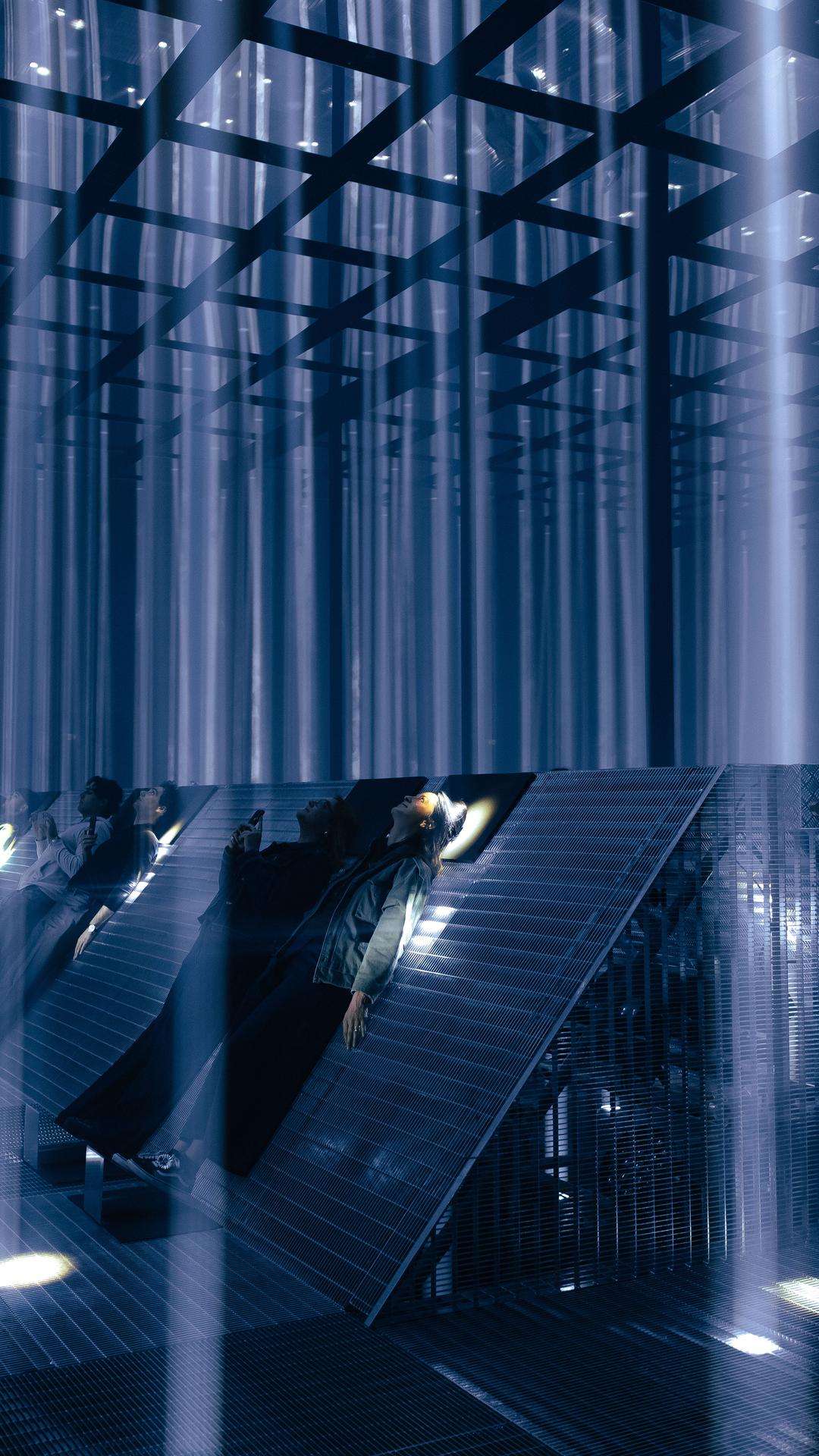

Promo photo of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in 'Bonnie and Clyde' (1967). Distributed by Warner Bros./-Seven Arts

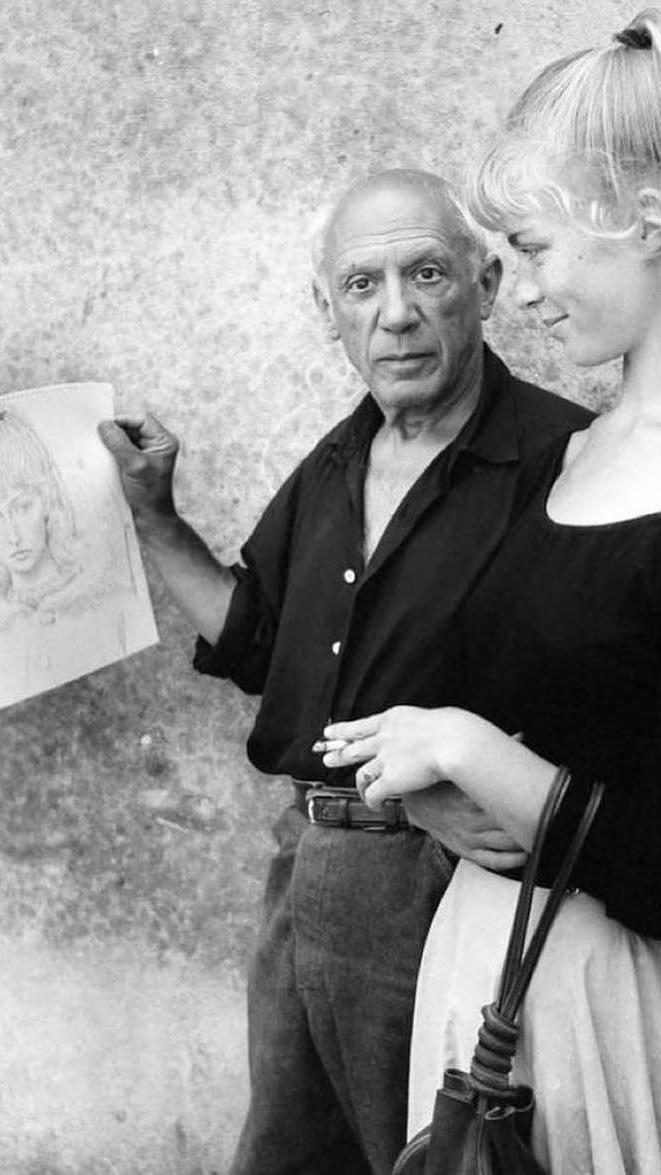

At the heart of New Hollywood was a shift in power from studios to directors. Inspired by European art cinema (especially the French New Wave), young American filmmakers demanded creative control and pushed formal boundaries. This was the era of the auteur, where directors like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Robert Altman didn’t just make films, they authored them. Each filmmaker’s distinctive voice and style came through in their work, in contrast to the old studio system that prescribed aesthetic and subject matter in production code restrictions.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/2b1b47bb2b9ff8597c9fb4a3aa09af92276b50e3-640x416.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=320)

Isabella Rosellini and Martin Scorsese by Wim Wenders (1984)

Stylistically, these films embraced raw, unpolished aesthetics: handheld cameras, natural lighting, improvised dialogue. A number of factors encouraged this style. Budgets were often smaller and filmmakers had to adapt to smaller crews and teams. More importantly, these stories were naturalistic and grounded, morally ambiguous and often bleak, and the aesthetics matched this. Iconic moments like the “You talkin’ to me” scene in Taxi Driver or the Graveyard in Mickey and Nickey felt like snapshots of real life, a stark contrast to the stilted black and white morality of the previous generation. Traditional heroes were replaced by criminals, drifters, and loners; flawed individuals caught in systems they couldn’t control. Violence wasn’t glamorized, but shown as sudden, messy, and psychologically disturbing.

This realism extended to the actors. The golden age glamour of Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn gave way to the intensity of Al Pacino, Gene Hackman, and Robert De Niro; actors whose performances often felt less like portrayals and more like personal exorcisms.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/6f0792810ac8516aa9a047ec0b28f6d285b7daf8-1222x1800.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=611)

Robert De Niro behind the scenes of 'Taxi Driver' (1976). Photography: Steve Schapiro

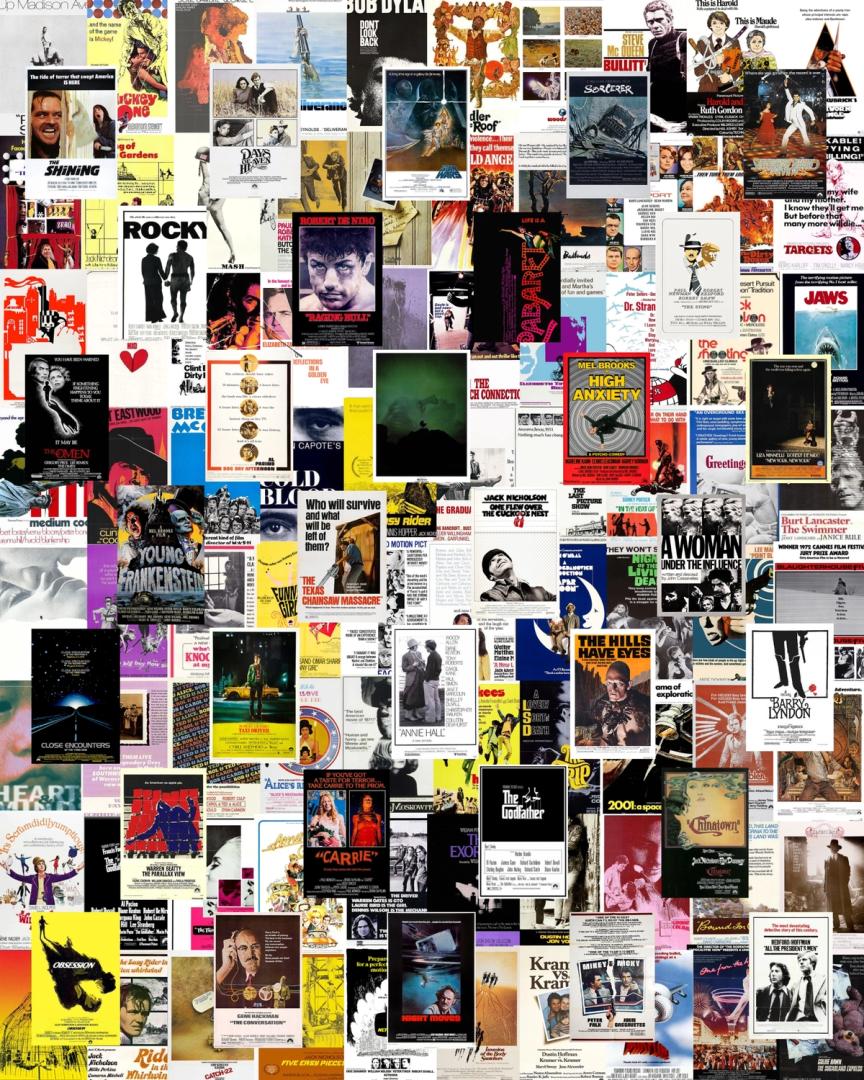

Films from the Era

Some of the most influential films in American history came out of this period. William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) portrayed a world of crime and corruption with a sense of documentary realism. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) turned the gangster genre into a multi-layered story about family, power, and American ambition.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/b3f38e57f1f7610d929a5287fdeb8d7b44746bb1-750x495.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=375)

Marlon Brando as Vito Corleone in The Godfather (IMDB)

Martin Scorsese was another key figure in the movement. His early films, like Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976), took viewers into the minds of alienated men living on the edge of society. These stories didn’t offer easy conclusions, but they resonated with people who felt similarly disillusioned.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/9ad47d32c07486820a439320009323fb5bf6825c-1400x934.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=700)

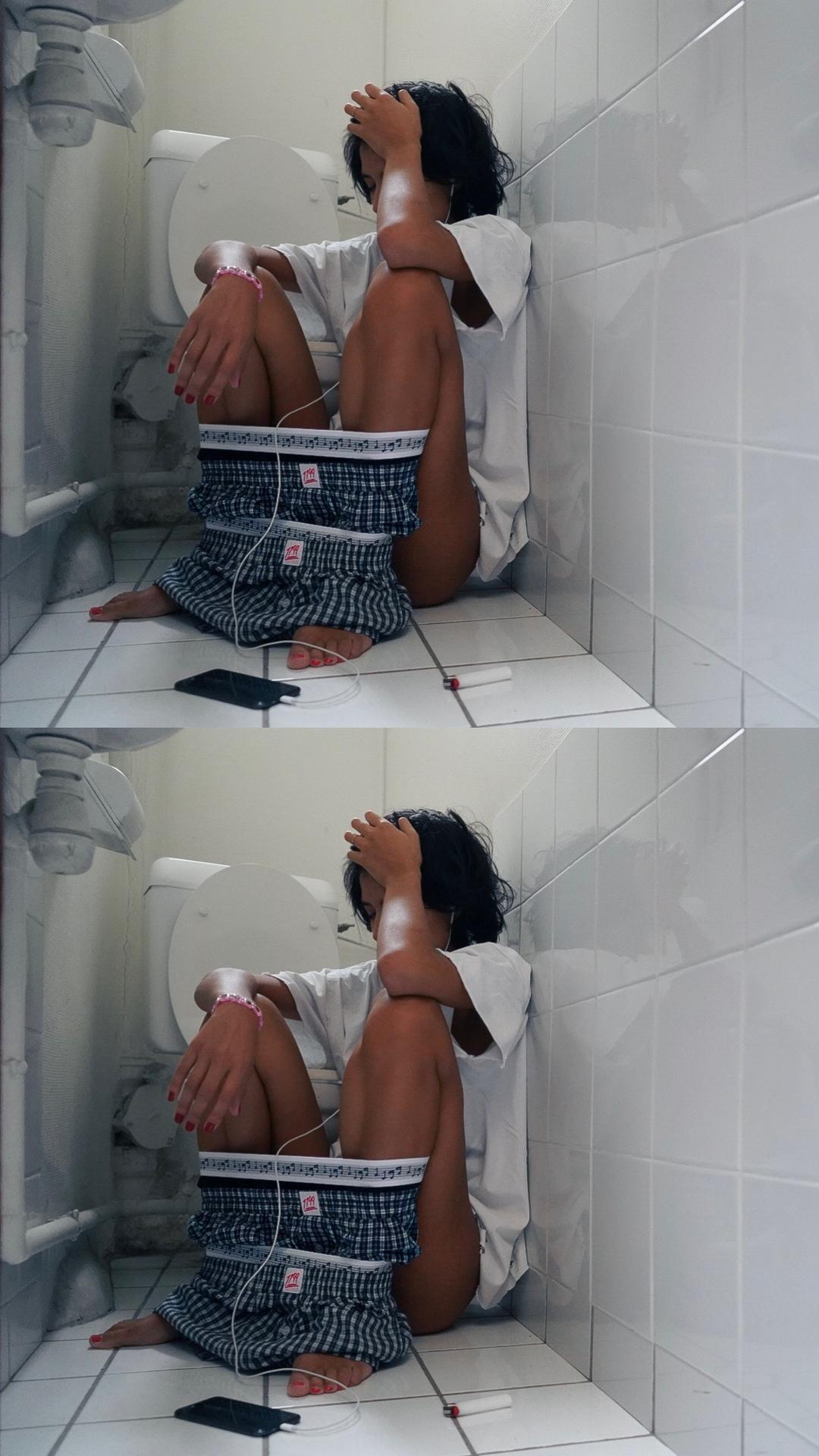

Behind the scenes of 'Taxi Driver' (1976). Photography: Steve Schapiro

Outside of the crime genre, filmmakers like John Cassavetes and Elaine May pushed boundaries in more intimate ways. A Woman Under the Influence (1974) explored mental illness and family dynamics in an unfiltered, emotionally intense way. Mikey and Nicky (1976) blended gangster tropes with deeply personal storytelling. These films were about human behavior more than plot, and they weren’t afraid to get messy.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/64251f4c6010f2a8570e804f14571673315b9fbe-1500x807.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=750)

John Cassavetes, left, and Peter Falk in “Mikey and Nicky,” directed by Elaine May.Credit. © Jumer Productions, Inc.

Why it ended

By the late 1970s, the freedom that had fueled New Hollywood began to disappear. Big studios had taken note of how successful some of these films were, but they also saw the financial risks. When huge productions like Heaven’s Gate (1980) bombed at the box office, it gave studios a reason to pull back control from the directors.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/4adf8509b4324d47257aee63bdf90d1da8f463b7-3800x2280.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1900)

A still from Heaven’s Gate. Photography: Ronald Grant

At the same time, a new kind of film was beginning to dominate. Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) were both massive commercial hits. These blockbusters didn’t challenge viewers in the same way as earlier New Hollywood films, but they were profitable. Studios began to favor spectacle over subtlety, and personal filmmaking took a backseat again.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/3d475e430223a29386fc1e250faeb3af902cdc17-715x475.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=358)

Star Wars filming in Death Valley

There was also the broader cultural shift of the Reagan era. In an interview with Vox, film critic J.Hoberman essentially summarises Reagan’s influence on Hollywood, “he was able to conjure up this imaginary past that was very appealing to people and that was already going on on TV with Happy Days, and in movies like American Graffiti”

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/c241b3a64bfff0845cf8a848d693d9ef901a59b9-1258x1600.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=629)

Happy Days / © American Broadcasting Company

The Aftermath

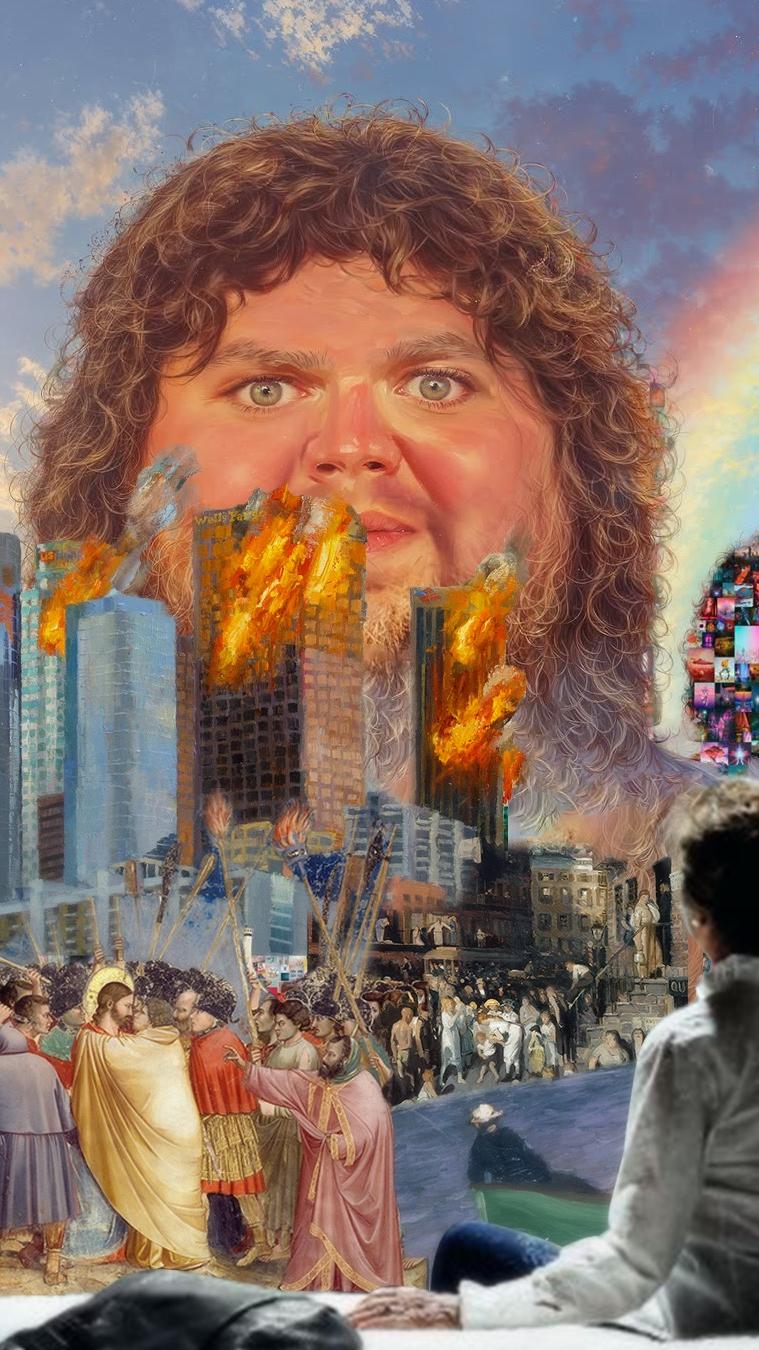

New Hollywood was a rare moment in film history when creative freedom, cultural upheaval, and audience interest all lined up. Even though it only lasted about fifteen years, its influence is still felt today. It helped pave the way for independent cinema and showed that audiences were willing to engage with films that took risks. Many of the directors from that time went on to have long, respected careers, and their impact can be seen in the work of modern filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson, the Safdie brothers, Greta Gerwig, and Barry Jenkins.

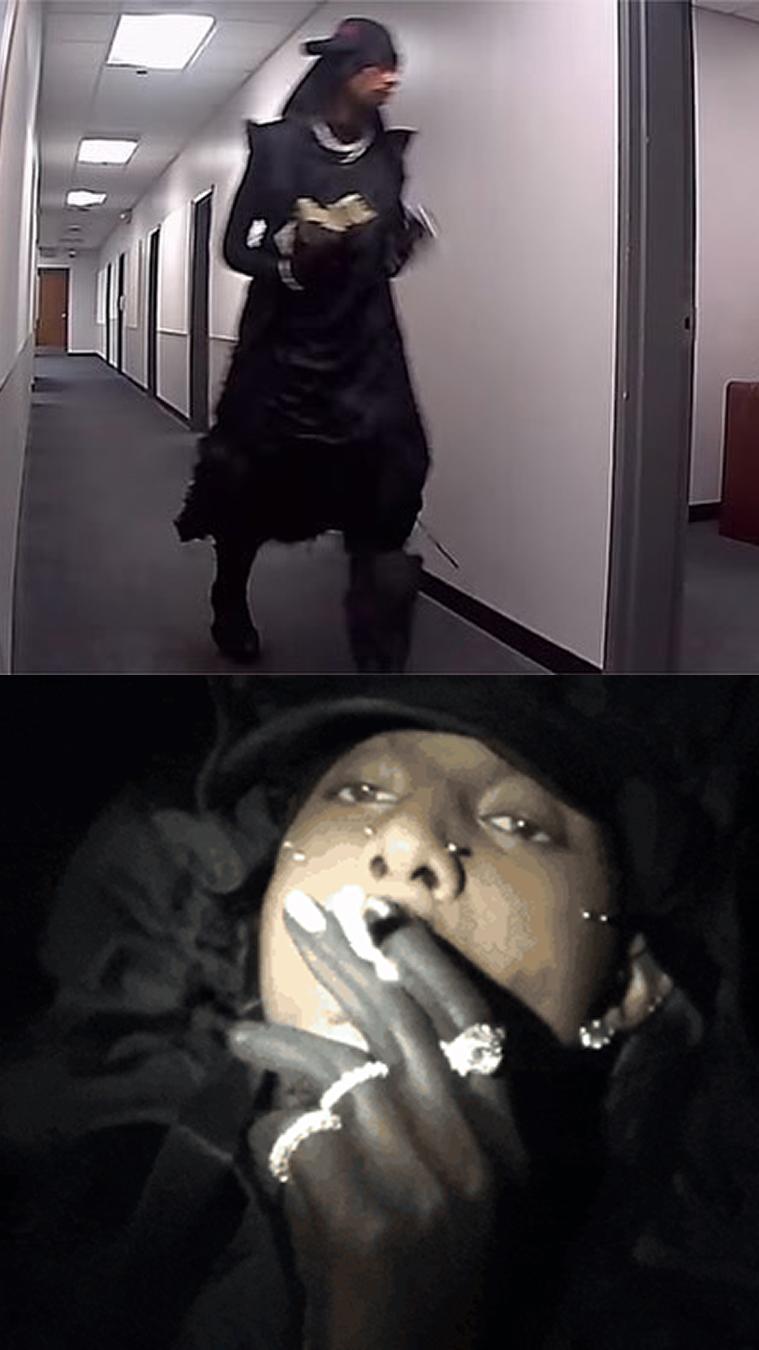

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/ed48ebfbe1594d828bb516ec919ed194e5c7574c-1600x899.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=800)

Adam Sandler in Benny and Josh Safdie's 'Uncut Gems' (2019). Photo: Julieta Cervantes/Courtesy of A24

More importantly, the movement proved that film could be both art and entertainment. It allowed American cinema to grow up, moving beyond simple morality tales and into more complex, emotionally honest territory. That idea has never fully gone away.

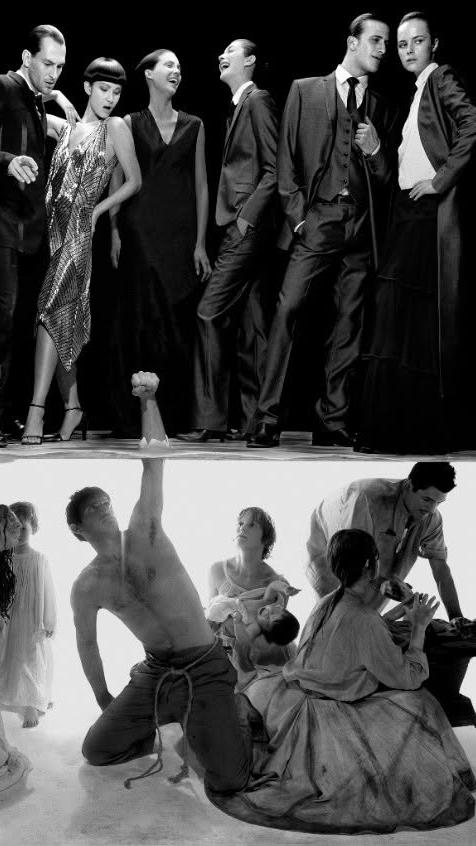

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/8876cf36c27dd04f11cf1d28303a2ddc03115400-1000x750.webp?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=500)

Paul Thomas Anderson directs stars Alana Haim and Cooper Hoffman on the set of 'Licorice Pizza' (2021). Photography: Mike Bauman

Written by Fares Akhaoui (@faresakhoui)

Image Curation by Carly Mills (@carly_monoxide)