How Recessions Impact Art

The relationship between a society’s economic health and its art is complex, dynamic, and contradictory in outcome. There’s the old saying that hard times make strong people, who make good times, which make weak people, who make hard times. It’s tempting to read artistic production into this same pattern. But hardship also snuffs, and leisure can be generative.

Anthony Baratier painting a landscape 'en plein air,' (2019). CC BY-SA 4.0

Obviously there’s no one answer to what social conditions optimize artistic output. The question itself is unfeeling and robotic. But today, in the early stages of what may or may not become a generalized recession, examining past recessions' impact on art is at worst an entertaining exercise, and at best might suggest what our possibly impending deprivation will do to a much maligned contemporary art.

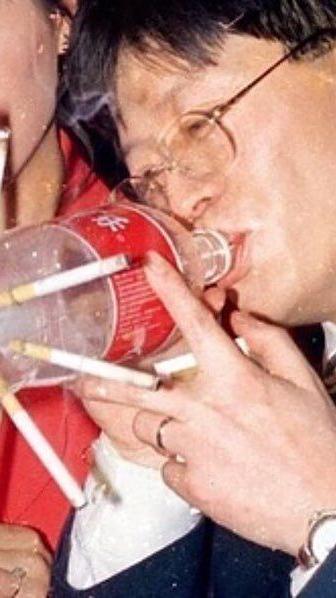

Six compiled recession headlines from April, image posted via Bluesky (@newseye.bsky.social)

Several qualifications are in order, the first being that the way we define recession today in a globalized economy bears little resemblance to a 1550s Florentine’s economic crisis, so consider the term loosely used. Also: in every case, the forces producing the art highlighted are not solely reducible to the proximal recession, obviously. And: the art highlighted is an informed selection, not an exhaustive survey.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Iolanda (2011).

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/ London.

Finally it’s worth saying that the suffering produced by recessions is very real, and societal hardship is not something to be treated lightly.

-

Arnold Böcklin, The Plague (1898)

A not entirely arbitrary starting point: the Black Death. A uniquely generative catastrophe that not only catalyzed new aesthetic sensibilities, but helped birth the market economies we know and love or hate today.

Miniature by Pierart dou Tielt depicts the people of Tournai burying victims of the Black Death (1353)

It’s difficult to articulate its decimation. Estimates are notoriously shaky, but suggest somewhere between 25% and 60% of Europe's population perished. This sort of culling does more than kill, and those who survived did so with altered worldviews.

The plague of Florence in 1348, as described in Boccaccio's Decameron. Etching by Luigi Sabatelli. CC BY 4.0

In many cases, this reckoning diminished faith in religious institutions, who had little they could materially offer the suffering population, and largely framed the plague as a hybrid mercy / punishment device depending on whether the sufferer was devout or fallen. Some religious leaders even instructed doctors to not interfere with what was clearly the work of God, and those who were more sensitive were still inept at addressing material hardship.

Giotto, Kiss of Judas (1304-1306)

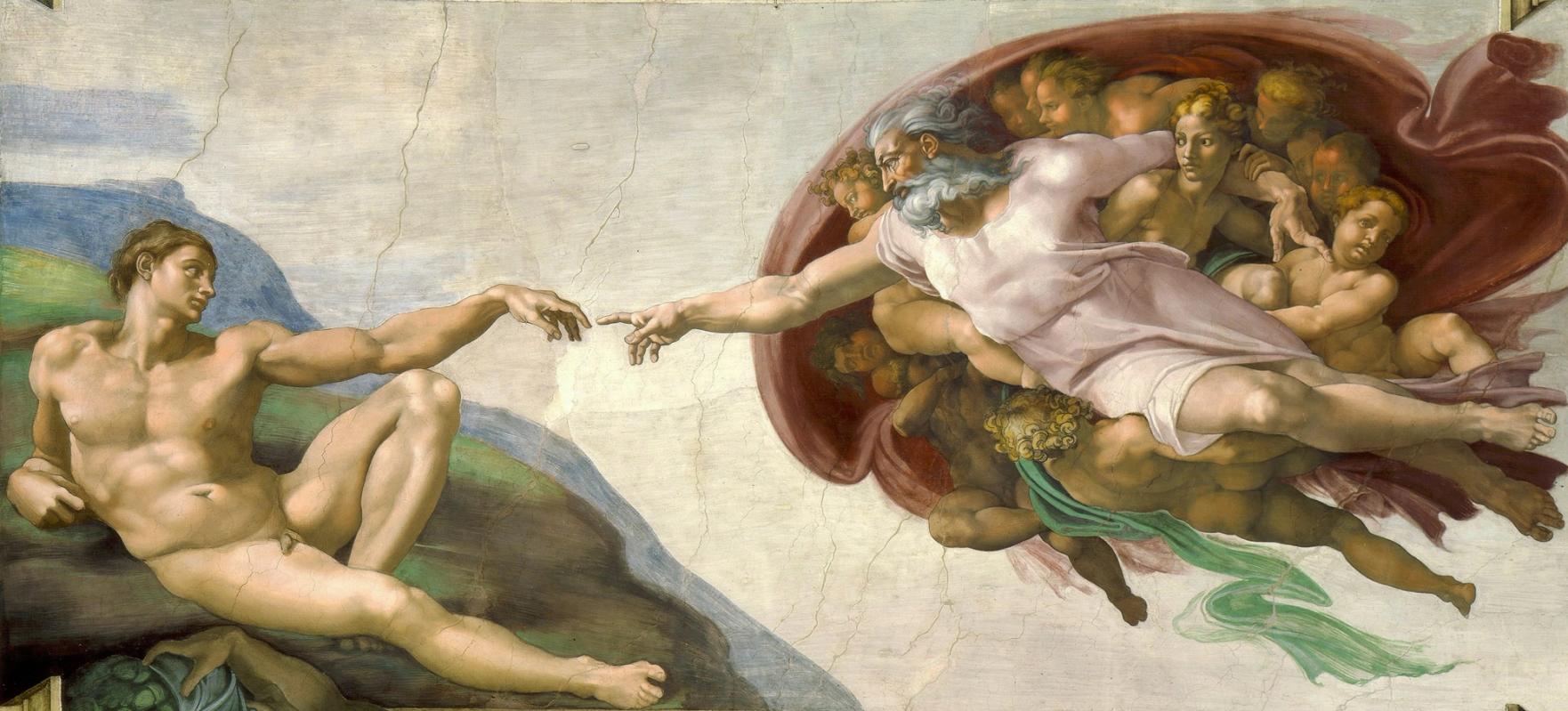

New criticality of centralized religion had an amplifying effect on the preexisting surge of humanism in Europe, which naturally found its way into art. While the Renaissance was ongoing before the Black Death (Giotto died before it even really picked up), a demonstrable turn towards the human subject in art emerged in the years following.

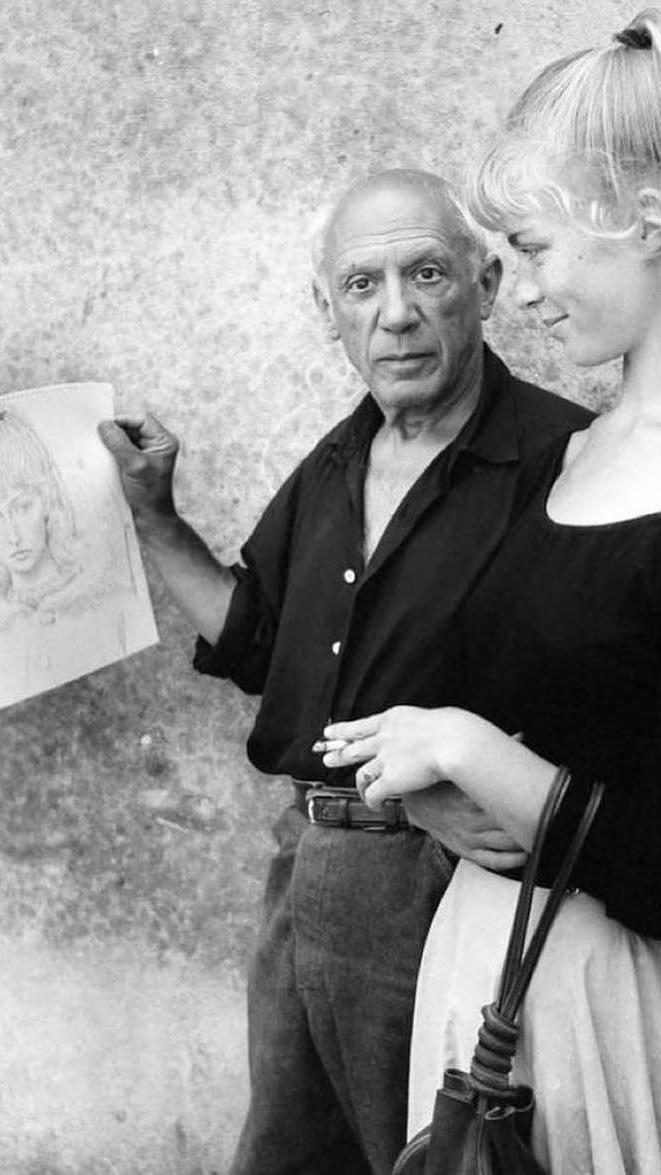

Michelangelo, Creation of Adam (1508-1512), fresco cropped detail

The Black Death produced the more specific focus on themes of mortality and the macabre. Memento Mori became thematically prevalent, and the Danse Macabre motif emerged. Again, these trends were percolating before the plague, which played an amplifying rather than generative role. The Triumph of Death fresco by Buonamico Buffalmacco, for instance, displayed an apocalyptic vision that at first would appear to typify the mood following the Black Death but actually predates it by several years.

Buonamico Buffalmacco, The Triumph of Death

The scale of the pandemic and the resultant labor shortage dealt a serious blow to feudalism, one it never fully recovered from. In this way, the Black Death was a turning point in the development of the market economy. There’s a lot that’s positive about the development of markets, but the majority of the hardships considered from here on out will be produced by them.

Sandro Botticelli, Primavera (1482)

-

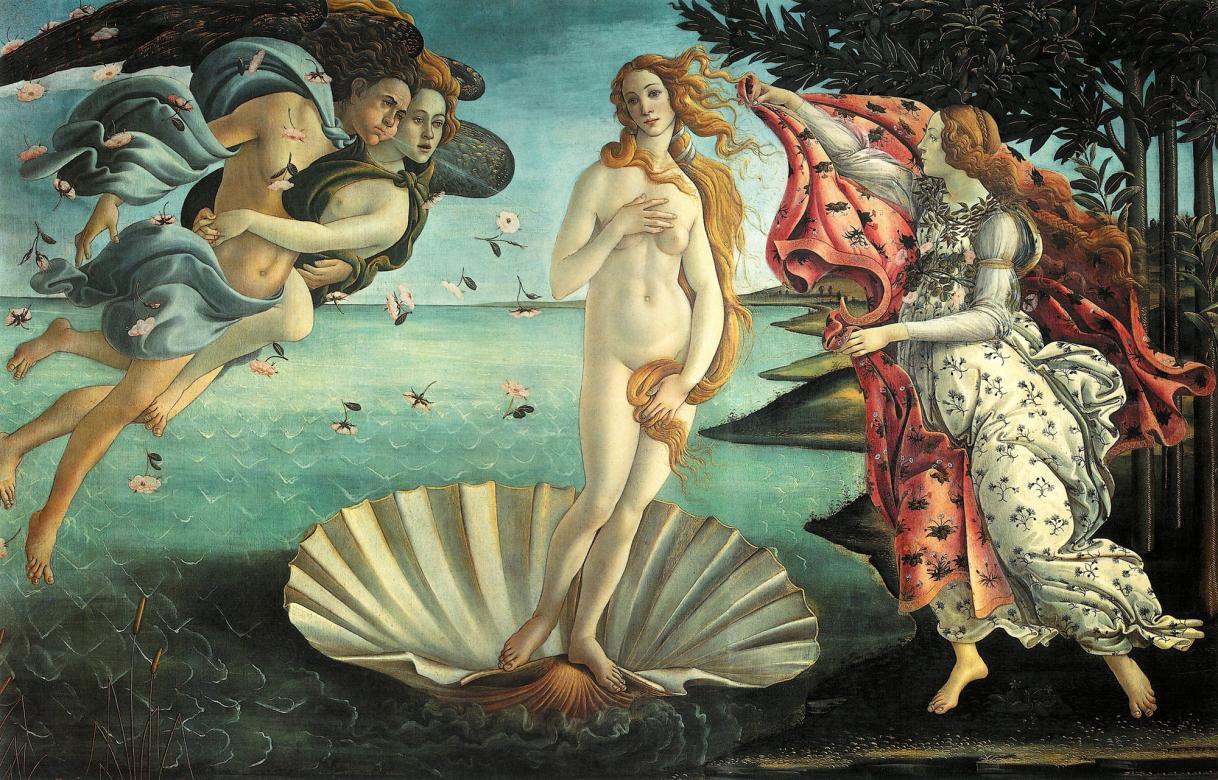

Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (1484-1486)

The Renaissance itself, coming in the heels of the Black Death, was a boon for the Italian economy. As the period waned, and rising powers with ports on the Atlantic shifted trade away from the Mediterranean, the economic conditions in Italy began to deteriorate, a climate worsened by a series of expensive wars and new plague outbreaks.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Journey of the Magi (1459-1461)

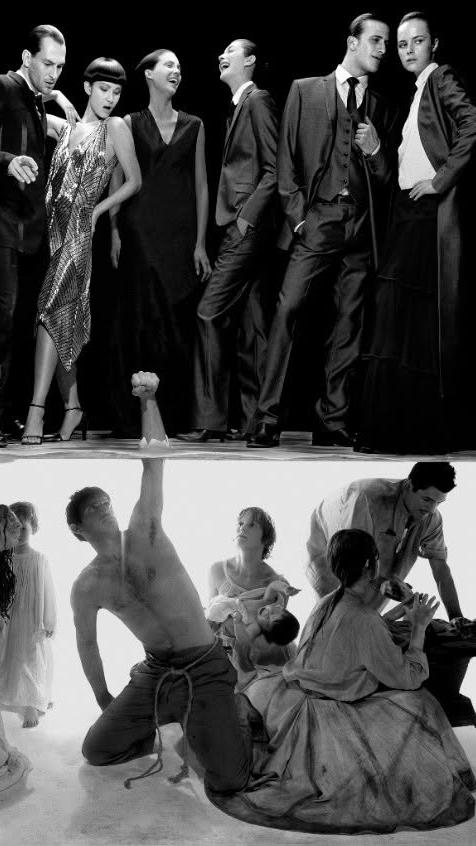

From this recessional context emerged Baroque painting. It’s an umbrella term for a range of styles, but is generally characterized as dramatic and intense both in subject matter and color palette. More extreme chiaroscuro and a tendency to depict the climactic moment (rather than the moment preceding the climax as had been the trend during the Renaissance) were both common.

Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598-1599)

While it would be convenient to link Baroque’s intensity to economic and social instability, its primary impetus was the Counter-Reformation. Spurred by the Protestant Reformation which threatened to steal their flock, the Catholic Church took an extensive look in the mirror in the mid 16th century, and one of the things they came away with was that they needed to be doing art differently. Powerful depictions and the avoidance of mannerism's stylistic weakness were emphasized. It was to be a populist art, painting that would move people.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/00aa578ca67b82927daa1a5f6914e50dad19f1d2-2048x1510.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=1024)

Jael and Sisera (1620) by Artemisia Gentileschi, a contemporary of Caravaggio and undoubtedly the most celebrated female painter of the 17th century

But this new emphasis by the church was enhanced by economic downturn. During the boom years the merchant class had become a major segment of the patron pie. When things got tough their money dried up, and the church became, again, the main game in town when it came to paying painters. Religious patronage’s renewed dominance led, of course, to works made in their image.

Caravaggio, The Seven Works of Mercy (1607)

But a mere proclamation by church officials to be more ‘direct’ is hardly responsible for the way this directness was approached. Caravaggio, for instance, worked with an edge informed by a childhood of deprivation. The energy of his tenebristic style is irreducible to a church decree, and several of his commissions were rejected for indecorum. Caravaggio’s work embodies economic hardship in another way–several of his major works, such as Death of the Virgin, used the poor, the homeless, or sex workers as models. And to look at Caravaggio's personal life it seems unlikely he cared too much about what the priests thought anyway.

Caravaggio, Death of the Virgin (1606)

In the nearby Netherlands, another master’s economic luck was about to turn. Despite being one of the consensus greats during his own life, Rembrandt couldn’t manage to keep money in the bank. He loved to buy stuff. Perhaps he was one of the weak people made by the good times.

Rembrandt, The Night Watch (1642)

Good times indeed. Living during the Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century, an economic boom period that produced a surplus of incredible painting, Rembrandt developed financial habits and a standard of living that even his fame could not support. An economic downturn following the Peace of Münster, especially during and after the First Anglo-Dutch War of 1652–1654, impacted his patronage network, a network he had already strained through personal disagreements. This was enough to send him into bankruptcy in 1656.

Rembrandt, Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633)

Rembrandt’s post-bankruptcy works display a shift toward more introspective and raw pieces, including many of his famous self-portraits. Where opulence and grandeur had defined much of his earlier work, such as The Night Watch and The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, later works such as Man in a Golden Helmet and Return of the Prodigal Son display an inward turn and unsanded emotion.

Rembrandt, The Man with a Golden Helmet (1650)

Rembrandt’s travails underline an important point to consider when examining the impact of recessions on art, which is that artists' individual financial conditions are not always in alignment with the general state of the markets. As economies become increasingly financialized in the modern world, this only gets more true.

Rembrandt, Return of the Prodigal Son (1668)

-

Robert Henri, Snow in New York (1902)

It was true in the US at the turn of the 20th century, not only for artists but for many, as rapid industrialization produced a grotesquely wealthy gilded class, a narrowly surviving working one, and a whole lot of space in between.

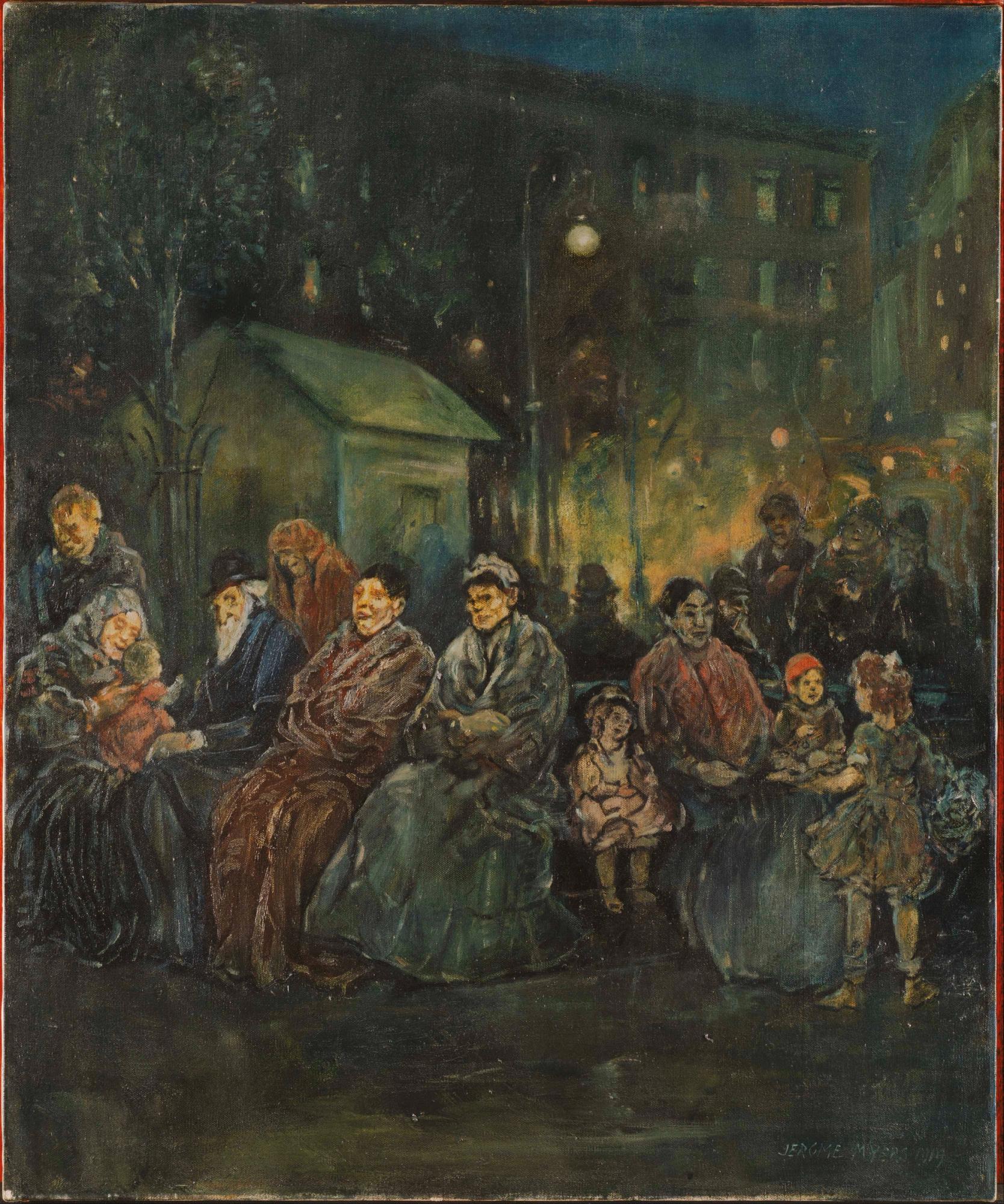

Jerome Myers, Night in Seward Park (1919)

The Ashcan School was a group of American artists working in the early 1900s whose work depicted these diverging conditions. The view of the world their works embodied was informed by the commoner’s economic difficulty during the age of the robber baron.

Ashcan School artists Everett Shinn, Robert Henri, and John French Sloan (1896)

The Ashcan School was never formally codified, and its name derived from a critical review several years after the style was developed. What united the artists was a desire to paint life as it really was, and reject the American Impressionism and academic realism that dominated the commercial art scene. Washing hung out to dry, workers in the pub after hours, the public street–these were the scenes of the Ashcan School.

George Bellows, Cliff Dwellers (1913)

It was deemed radical only briefly. Ashcan artists were destined to become old hat when the 1913 the International Exhibition of Modern Art, also known as the Armory Show, exposed Americans to the European avant garde. This show revolutionized the American art market and outcry against the Ashcan School quieted down quick.

George Bellows, Both Members of This Club (1909)

The general Ashcan project was taken up by an American wave of Social Realism following the Great Depression. A movement with similar foundations to the Ashcan School if different roots of lineage, Social Realism's goal was to show the true socio-economic conditions of the working class. This goal became urgent and popular following the Great Depression.

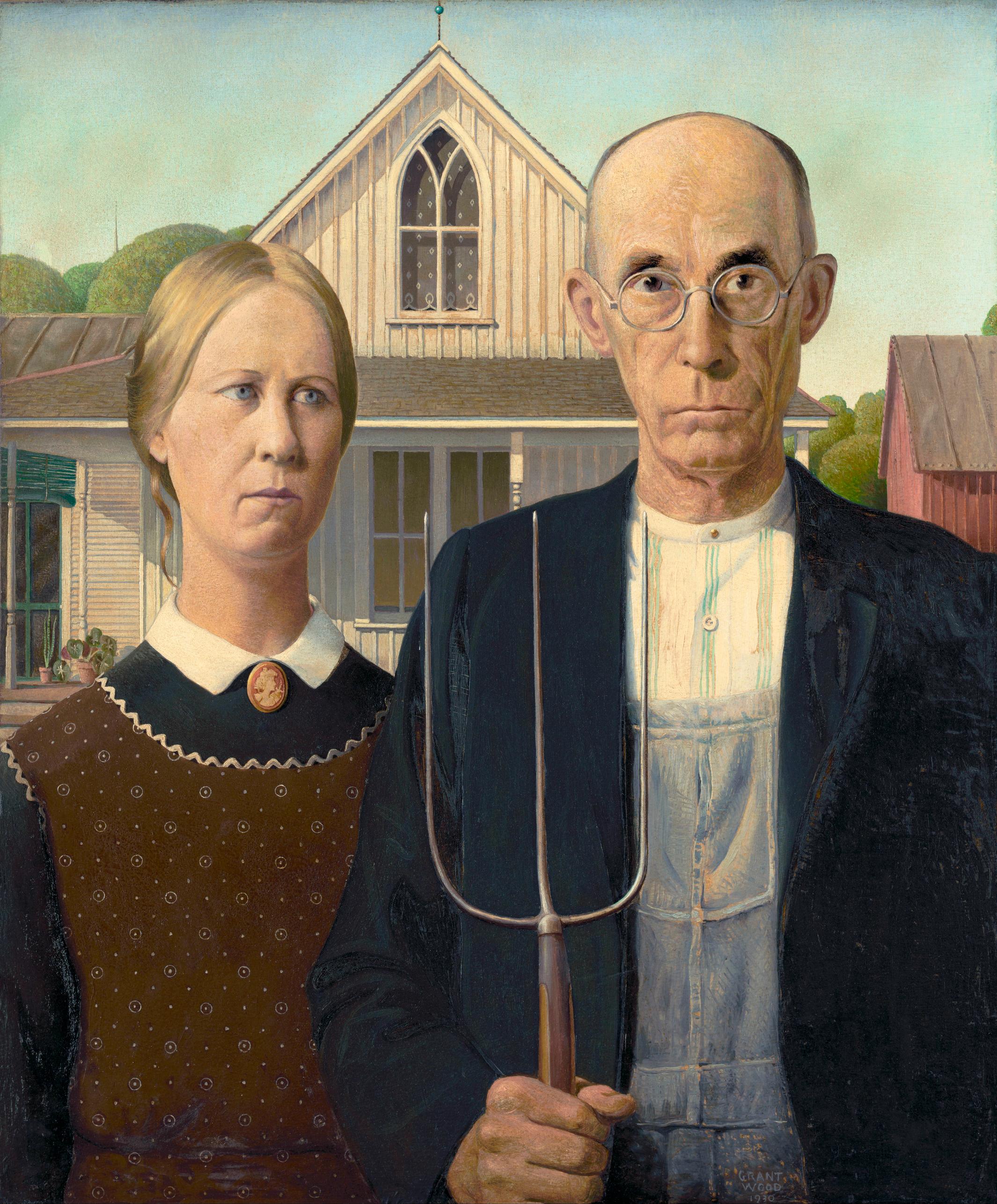

Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930)

Perhaps the most famous example of this style is Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Painted in 1930, it’s often read as a testament to the stout midwest spirit, a symbol of endurance through the hardship of the Great Depression, the modern pioneer. A closer look at the story behind the painting, however, reveals it may have actually been intended as a rural satire. But when the Depression intensified following its release, Wood leaned into the former interpretation, as it played to a wider audience and increased the work's value. Here, a recession led a public to expect a certain kind of art, project this expectation onto a piece that did not embody it, and prevail on the artist to conform their intention to this interpretation.

The philosophy of social realism extended to photography as well: This photo by Arthur Rothstein shows a farmer and his sons walking in the face of a dust storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma (1936)

-

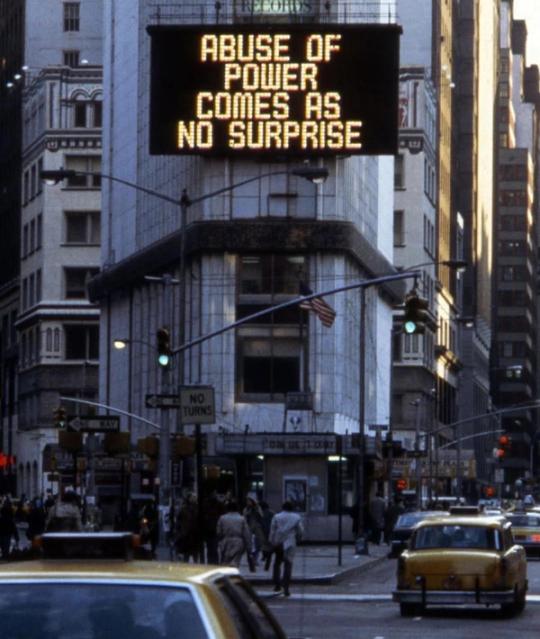

Jenny Holzer © ARS, NY From Truisms (1982). Times Square, New York, USA. Organized by Public Art Fund, Inc. Photo: Lisa Kahane

Increasing public awareness and understanding of financial markets, as well as the ability to critique them, began to percolate recession-responding artworks more directly critical of monetary institutions. After the dual recessions in the early 1980s, for instance, Agnes Denes's Wheatfield was a direct commentary on the development of commerce. Making art 'about' a recession increasingly took the form of art that questioned modernity.

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield - A Confrontation (1982). Photo by John McGrall, courtesy the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

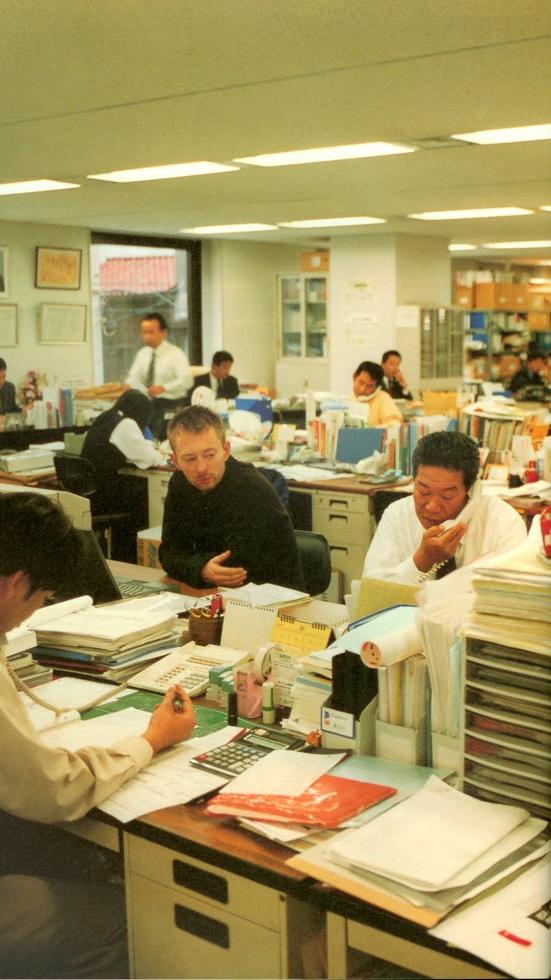

Consumerism was also increasingly drawing the ire of artists, and recessions provided a gasp of air with which to make the critique. In Japan, a redhot bubble economy burst in the early 90s, just as Takashi Murakami was developing his 'Superflat' ideology. An atmosphere of rabid consumerism, wherein art, pop culture, and commerce were flattened into one consumer experience, provided some of the foundational material for Superflat. The subsequent recession created a more reflective environment, where a collective loss of national identity and purpose allowed the Superflat aesthetic to bloom.

The 2008 financial crisis was also directly preceded by hot markets, and the art market was no exception. Artists like Damian Hirst, Jeff Koons, and Richard Prince were raking it in. At an auction hosted the same night that the Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, Hirst sold $111m of his own work. Those buyers would watch that value plummet in the coming months. Artists who were wildly successful just before the G.R. would experience lasting stigma, symbolizing the decadence of the pre-recession art world.

Hirst photographed with "For the Love of God" (2007), a platinum cast skull encrusted with diamonds - a memento mori. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Out of the Great Recession emerged an emphasis on social practice art, and critiques of capitalism and financialization, even as the art market itself became more financialized. Emerging artists like Josh Kline found a receptive audience for expressions of general economic dissatisfaction and technological anxiety. Increasingly, the public expectation

Josh Kline, Productivity Gains

The art market figured that if it was susceptible to the shocks of globalization, it might as well profit from it too. Turns towards new international markets, China in particular, broadened and diversified the network of art markets. Buyers were also increasingly aware of art as investment. The dollar bottom line and social prestige became more important.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/f166ba8c2211203bbc0bf74500419f0259d7b8b0-1296x1018.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=648)

Alex Schaefer, LA Skyline (2011) posted via Flickr

The Great Recession is the first recession for which we have any sort of robust survey data on how artists actually felt. A 2009 survey that solicited almost 6000 working American artists found that overall sentiment was actually fairly strong following the recession. While resources were low and fewer sales were projected, 9 out of 10 thought that artists had a ‘special role in strengthening communities during this time,’ and 75% of respondents thought it was an ‘inspiring’ time to be an artist. While this sentiment probably predated 08, its prevalence during that recession highlights a notable trend in artists seeing their vocation as having socio-societal importance. In this formulation suffering becomes romantic, and the ability to speak to the suffering of the larger society becomes an artist’s purpose and skill.

William Powhida, Market Crash (2007). Image courtesy of Schroeder Romero, New York.

-

The Covid recession is important not just because of the NFTs, but also because of the rapid digitalization of the art world. Galleries integrated digital platforms almost overnight. Entire auctions were conducted for work only ever viewed through a screen’s pixels. The proportion of art sold online skyrocketed and hasn’t come all the way back down.

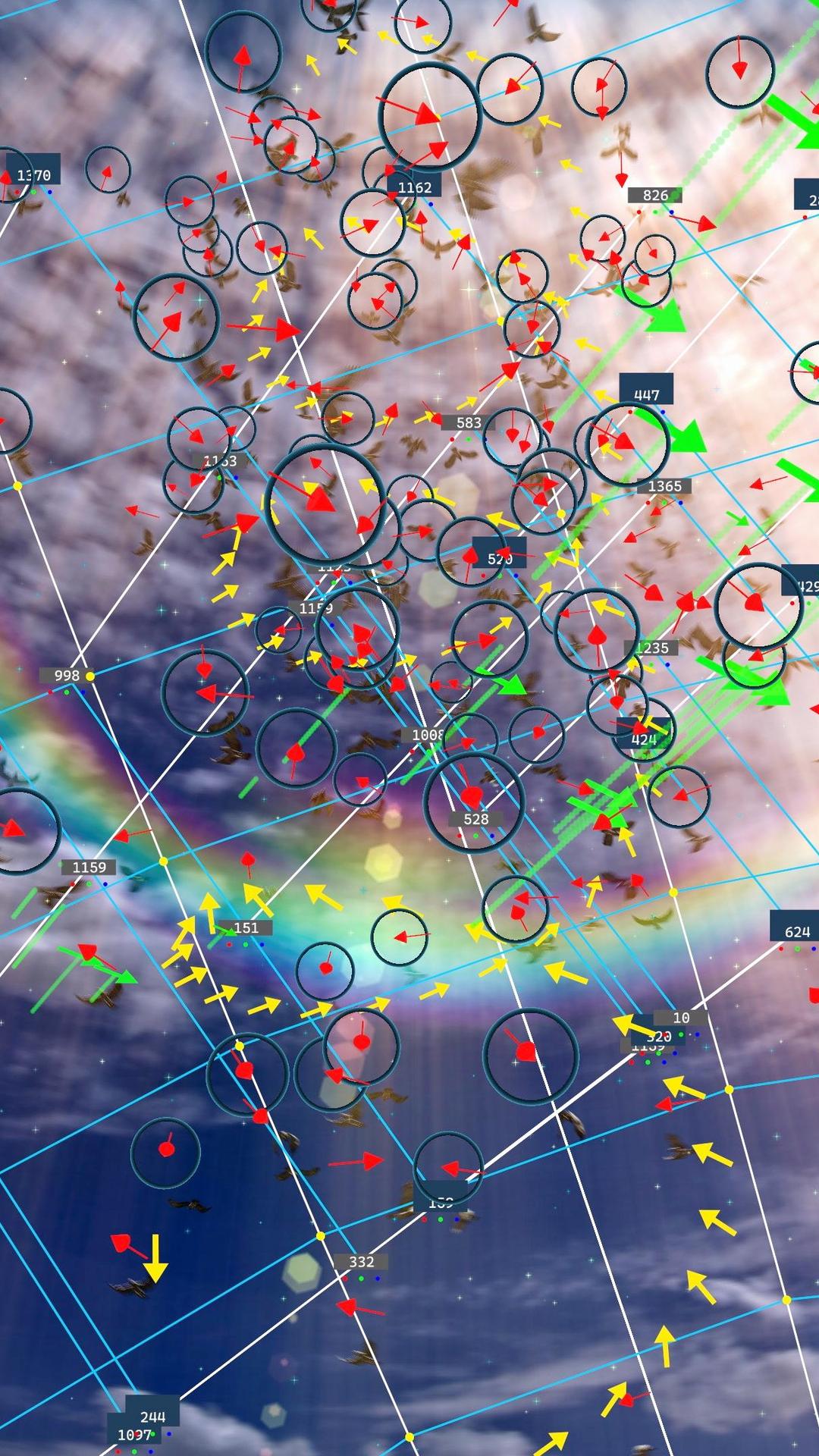

OnCyber is a digital gallery builder where you can display 2D and 3D NFTs. Image posted via X (@OnCyber)

Also though, NFTs. NFTs not only brought in millions for auction houses nimble enough to capitalize on them (Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days sold for $69m at Christies), but shook the foundations of digital art. The technical possibility of an NFT as a tool to cut out gallery middle men didn’t really pan out, but the NFT craze was a very developed form of art-as-investment. While the craze died hard, NFTs have survived, and are now clearly going to be a part of the art market of the future.

Beeple, Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021)

The NFT craze left an enduring stigma on certain art styles, but also seems to have amplified that (again) preexisting trends of the utilization of virtual images in fine art. Artists that covered in a piece on Early Virtual Aesthetics I wrote earlier this year like Gao Hang and Sasha Yazov saw their work take its current shape around this time.

Gao Hang's first NFT release from April Fools' Day 2021, an AR piece titled Ransom Money, pictured in front of the Wall St. Bull

Of course, the quarantine experience also made the Covid recession unique, and this uniqueness had particular effects on art. In 2025 it feels like we’re at peak wave of emerging artists in all fields who started during Covid. Established artists felt the squeeze too. A probably not entirely representative survey of 12 very successful artists by Artnet in March of 2021 displays a lot of common themes: the pandemic drove them inward, made them feel deranged, and led many to innovate their creative practice. While it has become cringe-inducing to mention the pandemic in the context of one’s art, an event that imposes on life in such a novel way is undoubtedly generative.

Sasha Yazov, Ghosts (2022)

-

And now our new recession. At the time of writing, the trade deals executed already and the ones rumored to be on the horizon make its likelihood and depth an open question. It could have structural impacts on the art market, which had only grown more internationalized since the 08 recession. While there is some statutory evidence that artworks could be exempt from tariffs, the larger breakdown of trust is a harbinger of a less stark but more permeating shift: diminishing US cultural hegemony. Wanting a piece of the cultural powerhouse accounts for several zeros on a lot of these international auction prices. When that desire lessens, and it will, so will sales.

"Keff Joons" (2025) installation by CJ Hendry, pictured with the artist. © Cj Hendry Studio

But that’s just market stuff. What can we expect on the ground, in the studio? Several trends have emerged from the preceding studies that we could consider. In general, I’ll apply them with a high degree of optimism.

A new recession could lead to an amplification of already existing philosophical developments, like the Black Death did. Perhaps calls for decommercialization and depoliticization will be heard by new ears. Growing distrust of the government and global market could lead to a refocusing on direct community which may be productive for art.

Raphael, Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1507)

The recession could also change the patronage landscape like we see in post-renaissance Florence. Fewer international buyers could lead to a renewed focus on production for domestic markets across the world. Art may begin to not feel so stiflingly international, homogenous.

Caravaggio, Ecce Homo (1605)

It could certainly deal a number of successful artists a serious financial blow. Perhaps they, like Rembrandt, will turn inward, check their hubris, discover new styles, enter their ‘late’ periods.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait with Two Circles (1665-1669)

As the Ashcan school committed to depicting life of those left out of economic boom times, maybe an artistic movement will emerge which focuses on portraying the two ends of the diverging economic system. Supposedly, the economic has been great for several years, but it doesn’t feel that way to most of the people I know.

George Luks, Fishermen (1920). CC0 1.0

Social Realism never really went away. A shocking amount of the photography in the New York Times would probably qualify. It was always an ostentatious movement, but its emergence following the Great Depression does suggest that the taste and desires of a market may shift, may begin to want something new. The idea of us wanting something new from art is an uplifting one.

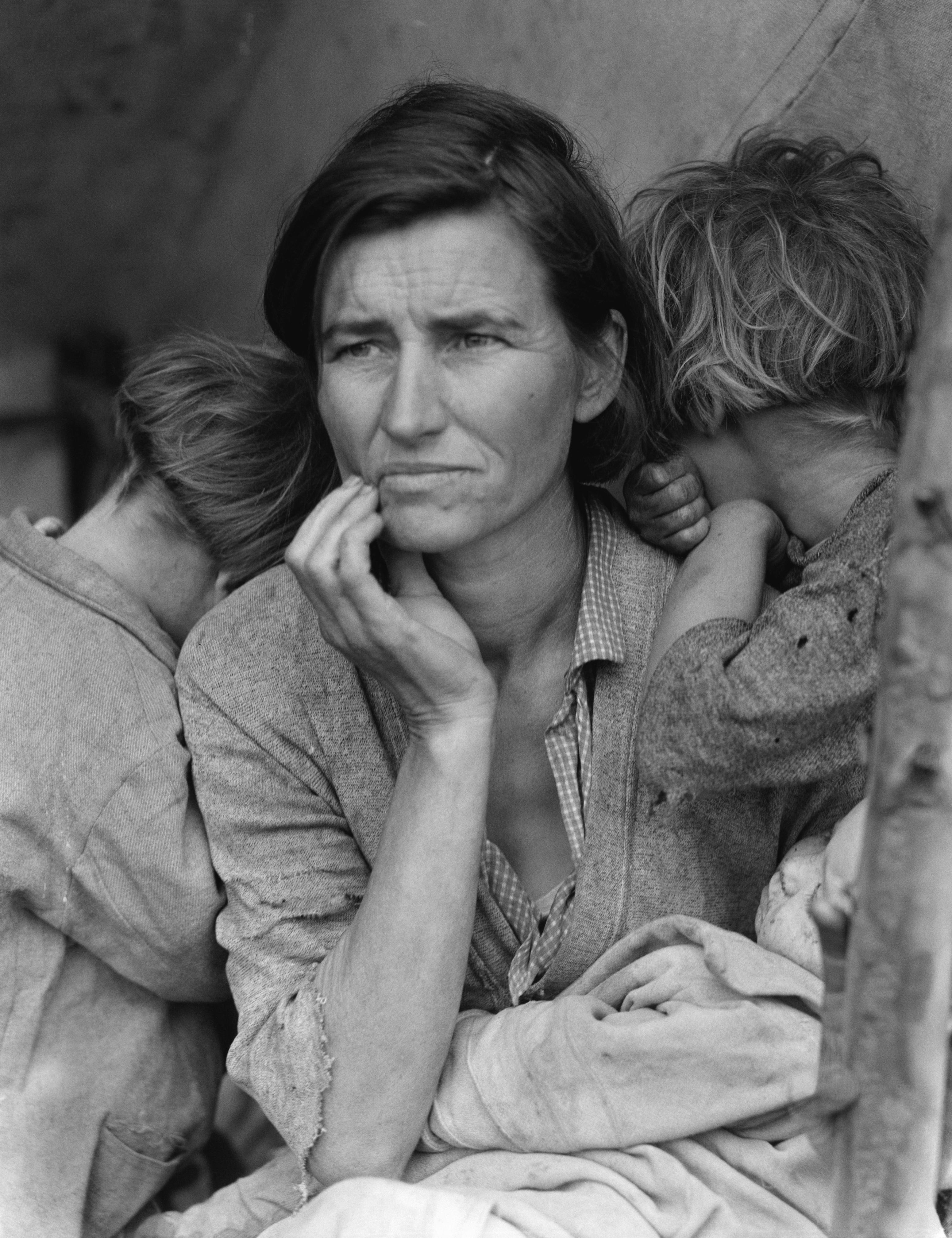

One of the most exemplary and recognizable pieces of social realism photography, Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother (1936) has influenced a century of journalistic photography

The market broadening and increased financialization in art during the 08 is a technical possibility. If conventional industry assumptions about the cost of importing artworks through conventional channels breaks down, NFTs look a bit more attractive. And just as the Covid recession saw an uptake of new technological integrations, the current state of AI means it is inevitably going to become more prominent, a trend exacerbated by an economic climate that makes its relatively affordable tools more attractive to artists who might not want to splurge on anachronisms like paint and canvas.

Sougwen Chung, ䷰ terrains of unknowing, (2022). Gillian Jason Gallery

Also like these two more recent recessions, it is possible that art will double down on its political engagement, that artists will only become more tragically aware of their goal in the socius. The positive way to spin this is that it may finally lead to some good political art. Nothing about political art is per se bad, it’s just that the political art being made right now happens to be.

Beeple's take on the JD Vance memes from March of this year, posted via Instagram (@beeple_crap)

The story of art and recessions is also, clearly, a story about markets, patronage models, financialization, globalization, the activist status of the artist, the artist’s tools, and the collective philosophy, at least. The ways a recession impacts art depends greatly on the structure of the society it finds. Ours, in which artistic production has been nearly entirely captured by the commercial market, and a grotesque media frames who pursues and succeeds at becoming an artist, and a living in noncreative employment while making art on the side is either out of reach of too unglamorous for many, and the collective exhaustion with the state of art ratchets higher daily, is due for a shake up. Whether it’ll get it, time will tell, eventually.

Written by Noah Jordan (@nnoahaonn)

Image Curation by Carly Mills (@carly_monoxide)