Martial Aesthetics

The forms, representations, and rituals of conflict

War has been ceremonial for as long as it has been. Mythologies, intentional design, and ritualized symbols are rarely far behind bullets, bombs, arrows.

A mix of intention and practicality, form and function, victory and death, the aesthetic network of armed conflict has captivated the minds of citizens, creatives, and tyrants for all of recorded history. Martial aesthetics are inseparable from warmaking, and go beyond guns and uniforms–representations of war, its related symbology, and societal ceremonies that invoke it are all part of martial aesthetics.

Martial aesthetics can be lipstick for a gruesome industry, frequently deployed to manufacture consent for its horrors. But the state does not have a monopoly on their use, and some of our time’s strongest pacifist impulses have emerged from the martial aesthetic framework. Martial aesthetics are a complex ideological theater of conflict, where motivations ranging from bloodthirst to heartbreak vie for the minds of subjects, citizens, and generals alike. Understanding their structure and their functioning is a necessary first step in resisting their implicit proposition, which is sometimes further bloodshed and destruction to serve the ends of demagogues, elites, and corporations.

-

We can think of the martial aesthetics as consisting of several layers.

The first concerns what is utilized directly in warmaking, from objects like uniforms and equipment, to incidental grandeurs like the dark gleam on the hood of an SR-71 Blackbird, to destructive forms like artillery and weapon discharge.

In the second layer we have depictions of war in photography, fine art, film, and literature.

The third contains the symbolic and ritualistic products connected to war in the abstract, such as memorial monuments, national ceremonies, and choreographed parades.

Layer 1

Transportation, a logistical necessity for any military, is one of the most visible touchpoints of martial aesthetics. Think the gilded or pelt-coated chariots of the Bronze Age, the steel masts of maritime seacraft (such as the Amerigo Vespucci, proclaimed the world’s most beautiful ship), the aerodynamic noses of ultrasonic aircraft.

The aesthetics of transport sometimes aim to intimidate. The dragon heads of Viking Boats, or the spike-mounted chanfron worn into battle by horses, or even the use of war elephants (a completely impractical mode of movement in actual combat) are examples.

But means of transport are primarily designed for function. The design of Lockheed’s U-2 (pet name: Dragon Lady), in all of its wide wing and darkly pointed expressivity, exemplifies the aesthetics of pure performance. Motivated by the need to achieve extreme altitude for intelligence gathering, the U-2 can cruise at 70,000 feet, making it basically impossible to target.

Kelly Johnson, a team leader at Lockheed’s Skunk Works who was a key engineer on both the U-2 and SR-71 projects, had a motto for his workers: “be quick, be quiet, be on time,” wisdom which applies equally to the aircraft he created.

Another functional aesthetic is that of stealth. Most are familiar with the B-2 Spirit, the heavy strategic stealth bomber, if only for its flyovers of major sporting events. For this aircraft, fuselage and tail were scraped, and low-observable technology was combined with high aerodynamics to offer both speed and near invisibility at certain angles. Discretion was part of its production–factory workers were sworn to secrecy. The B-2 is slated to be replaced by the somehow even sleeker B-21 in the early 2030s.

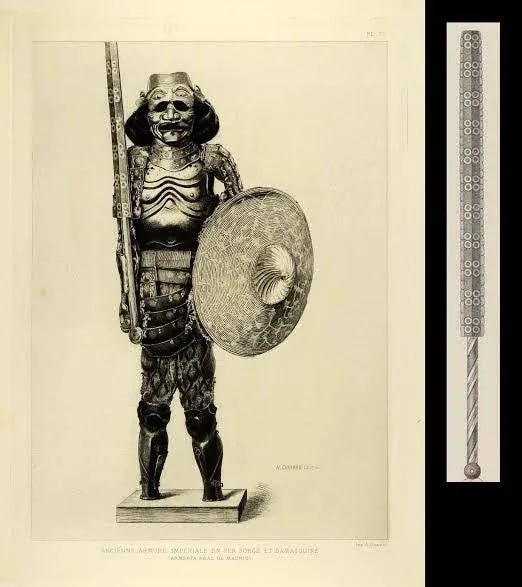

Weapons are the sharp end of Layer 1, with ceremonial as well as practical significance. Look to antiquity: the macuahuitl was a weapon used by multiple civilizations in Mesoamerica prior to Spanish conquest, and featured prismatic obsidian blades embedded into a wooden club, which was itself sometimes inscribed with designs. The sabers of the Napoleonic Wars were hardly less ornamental, especially in their later utilization, with some armies carrying them through World War II.

The actual deployment of weaponry is an aesthetic font as well. Consider the AC-130. Its ‘Angel of Death’ nom de guerre references destructive prowess, but also describes the look of a defensive countermeasure: the deployment of flares to confound surface to air missiles. Dozens of charges fall blazing from each wing and dozens more directly downward in a stunning pyrotechnic display which leaves in its wake a cyclone of smoke, four-pronged and curling like the wings of an angel, or a buzzard.

On the emotional significance of a mushroom cloud, I’ll defer.

Soldiers themselves are part of martial aesthetics, as is what they wear. Uniform design is big business; the Pentagon spends tens of millions of dollars on design costs. The development of new camos takes years. This is no modern luxury–16th and 17th century generals shelled out enormous sums on uniforms with little practical return because finer threads kept morale up. Still do.

Layer 2

Most of us have never set foot on a battlefield but we all think we know what war is like, even how it has evolved over time. Most of that knowledge comes from the second layer of martial aesthetics, representations of war in various media.

War photography is the primary direct conveyance now, but before that it was painting. The job of itemizing the best of them would require a lot more than its own article. But a few subjective favorites follow.

Albrecht Altdorfer’s The Battle of Alexander at Issus, painted in 1529, depicts the 333 B.C. Battle of Issus in which Alexander the Great claimed victory over Darius III of Persia. Its portrait orientation is unusual for a war painting, especially because Altdorfer was an incredible landscape artist.

Jan Matejko was a vocal proponent of ‘history painting’, a since abandoned genre defined by the scenes of representation rather than style or period. His Battle of Grunwald was painted more than 400 years after the battle it depicts. The frenetic composition took 8 years to paint, and according to one French critic viewing it in 1879, should be studied for 8 days to fully appreciate its largesse.

Elizabeth Southerdern Thompson, professionally ‘Lady Butler,’ was a prominent war painter in late nineteenth century Europe. Working at a time of swelling romanticism, her works balanced realism of detail with drama of content. She favored the moments before and after direct conflict.

Adolph Northen’s Napoleon’s Retreat from Russia is a heartbreaker. The German painter was neither prolific nor famous, but did matriculate at the Düsseldorf School of Painting, a well known group whose work was generally characterized by fine detail and the influence of the German romantic movement, both of which we can see here.

Many works, particularly those during and following the modernist movement, have strayed further from realism in their attempts to depict war. Umberto Boccioni’s The Charge of the Lancers, painted in 1915 is one example. Boccioni was a Futurist, so the emphasis of the mass of the horses in this work is somewhat unusual, but very effective. Boccioni died three years later, trampled to death by charging horses.

Of course there’s Picasso’s Guernica. There are many photos of the bombing at Guernica, but this is the image that has come to define the event in the collective mind.

Thomas Lea was an illustrator and war correspondent who painted a first hand account of WWII for Life magazine. His assignment was unusual, as Life was known for being a photographer’s journal. For Lea, paint wasn’t just equal to photography, but the only medium that could reliably convey what he saw while deployed.

War photography took up as early as the 1840s and over time became a self-sustaining factory of martial aesthetics. While there is theoretically less room to romanticize, photography is an enterprise every bit as selective as painting. Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima and Raising the Flag over the Reichstag are examples of images successful in their glorification.

War photography has also been marshalled to foment antiwar sentiment. When the cold-eyed fidelity of photography is used to portray horror and atrocity, martial aesthetics becomes a zone of ideological conflict. The way war is represented to the population can threaten the narrative a state sells to its subjects.

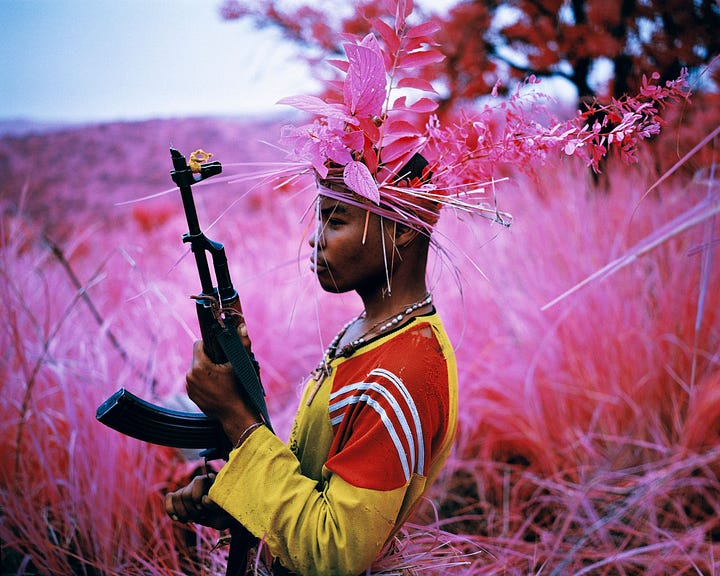

In recent years, new ways of depicting conflict have become increasingly common. A famous example is Richard Mosse’s Infra: Congo. Captured on infrared film Aerochrome, the same film used by the military to identify camouflaged targets, Mosse’s images are vibrant, surreal, and entirely defamiliarize one of the most intractable conflicts of the time.

Other attempts to redefine martial aesthetics delve into the more intimate moments in the lives of deployed soldiers. Tim Hetherington’s photo series “Infidel” (2010) depicts troops based in Korengal Valley which was considered to be one of the most dangerous postings in Afghanistan at the time. Hetherington shows the soldiers at rest and leisure, or whatever partial versions of those they were able to enjoy on that particularly dangerous deployment.

Sometimes, no single photographer is behind the dissemination of martial photography. Swim Call, the naval tradition of taking an open-ocean swim, has gone viral in the last year, and images have been sourced from all over the internet.

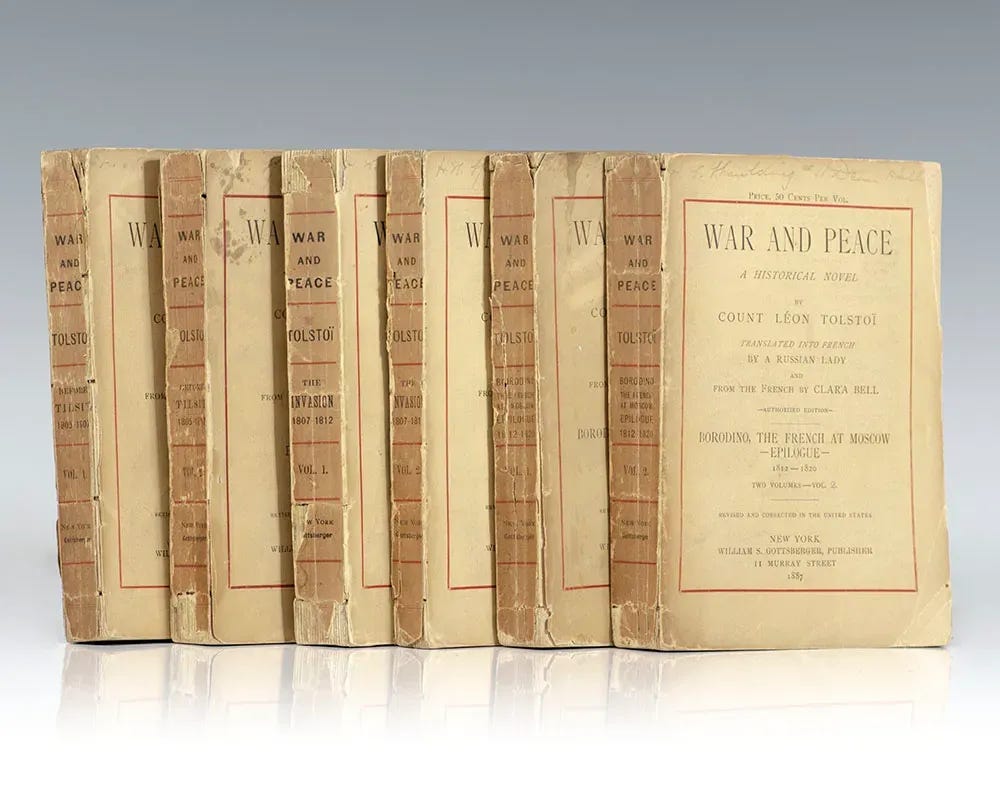

In literature, we have no end of war novels although certain monumental works stand out. At their best, such works manage to convey novel angles on the experience of war. Novels like Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried might do this through first person accounts that challenge conventional narratives about major conflicts. Tolstoy’s War and Peace attempts an audacious bird’s eye portrayal of the Napoleonic wars.

Film and TV, of course, are the source of most contemporary representational martial aesthetics, for most of us at least. It is also the mode of martial aesthetics we are most familiar with here, and will therefore be largely omitted. Feel free to go watch the news, Band of Brothers, or 1 in five movies on most major streaming services.

Layer 3

Beyond the dissemination of representations of war, though, a state (and a society) goes to great lengths to embed martial aesthetics to general civic life. Monuments, museums, cemeteries, and exhibitions are some of the main ways to do this. Designed to compel as much as inform, these instances of martial aesthetics are generally highly curated and controlled by the state that funds them.

The Didgori Battle Monument is a major cultural landmark in the country of Georgia, built in the location of one of the most consequential battles in the nation’s history. The memorial complex’s most striking features are the massive metal swords thrust blade-down into the hillside. The swords resemble crosses, reflecting the deep Christian roots of the region.

One of the most sacred exhibitions of martial aesthetics in the US is Arlington National Cemetery. A final resting place for many who have served in the US army and home to several famous monuments (such as Tomb of the Unknown Solider), Arlington is also a major tourist attraction.

At the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier we find another key piece of martial aesthetics, the ceremonial changing of the guard. Highly specific choreography is observed during this replacing of one guard with another, in footwork, gun-handling, and posture. Any visitors present must stand and remain silent for the duration.

Guard changing choreographies are not unique to the US, nor are they most pronounced there. The Evzones of Greece, for instance, show a bit more flair.

Uniting all of these disparate aspects in one physical location happens rarely, generally at a scheduled parade. Historically such assemblies allowed the higher ranks to examine the health and strength of their army. Now, they are a show of strength, and an appeal to national unity. High knees marching, aircraft rolling, big guns toting, all to the pounding of a drum.

The military has an obligation to compel. To justify its costs, both monetary and humane, it returns a swell of national pride. Martial Aesthetics are central in this exchange. When a nation asks the ultimate price of its citizens, it makes the request in beauty and drama.

Famed critical theorist Walter Benjamin wrote extensively about the aestheticization of politics, and the ways in which regimes can reframe their destruction as an aesthetic experience. Nowadays, they sometimes don’t even have to. As the array of global conflict complexifies, countries like the US engage in obscure proxy conflicts that receive no domestic portrayal at all. The martial aesthetic most effective at achieving the state’s goal (a world willfully ignorant to its crimes) is one of perfect absence.

But there is more in martial aesthetics than propaganda. There is also honor and courage, testaments to human innovation and progress, vestiges of culture, true artistic achievement. Such things are rarely pure. Nor are they in this case.

Image Curation by Erild Kondi (@kondierild)

Written by Noah Jordan (@nnoahaonn)