What's Really Killing Art

Art’s imminent death is proclaimed every so often. Right now, it’s supposedly dying very frequently. These narratives vary in their reasoning but hang together in shape: AI or the economy or the Art Market or Instagram or politics, a blackclad executioner’s axe hovering over an otherwise healthy neck.

The state of Art and The Artist today are worse than these fragmented panics suggest. The executee is actually deathly ill. Specific gripes about new technologies, social dynamics, or market issues obscure more foundational existential threats like the degradation of idle time, changing relationships to commercialization, and the commoditization of selfhood. These macro pressures are the subject of today’s Quick Thoughts.

—

Consider first the fact that since the 1980s, a neoliberal policy regime has shrunk public funding for the arts, lowered the wage floor, and increased the cost of living. Uncommodified time and energy have diminished. It’s harder to support a profitless art practice with an unglamorous day job today than it was 50 years ago, and the NEA won’t cover your studio rent.

So how does The Artist keep a roof over their head? Some make it into the Art World and sell work there, but that’s an environment whose gates of entry open for only a few and usually for reasons other than the quality of their work. For most creatives, commercial work is the only viable way to make a living. The work a corporation will buy does not commonly overlap with work that is good.

Another income stream is through commissions. The places to get commissions are social media platforms, platforms that are increasingly replacing museums and galleries as the primary way people see art. The Artist is incentivized to make art that will perform on social media. In other words, art for the algorithm. The algorithms do not care about good art, something we can easily surmise from the work that succeeds on their platforms, and the fact that almost none of the massive profits they’ve generated have been redirected into public institutions that support the arts.

But these structural problems are only part of The Artist’s plight, and apply just to those who are attempting to support themselves making art. The best art often crashes in from the margins, and while those margins are squeezed today, they are not nonexistent (more on that in a moment). Unfortunately, the frontier of art’s degradation is The Artist’s mind itself and applies equally to amateurs, dreamers, and non-professionals.

The Artist, like the rest of us, is subjected to the cult of self-actualization that defines our approach to work, passion, and self. Also rooted in the neoliberal paradigm, the idea of self-actualization is a natural byproduct of the narcissism and materialism that a system whose existence depends on its ability to sell consumer products fosters in a population. We’re told we can be (buy) anything, an ‘anything’ that is generally defined by material abundance and social prestige. What’s branded as a holistic and personal journey actually intensifies the fetishization of socially defined and memetic versions of success.

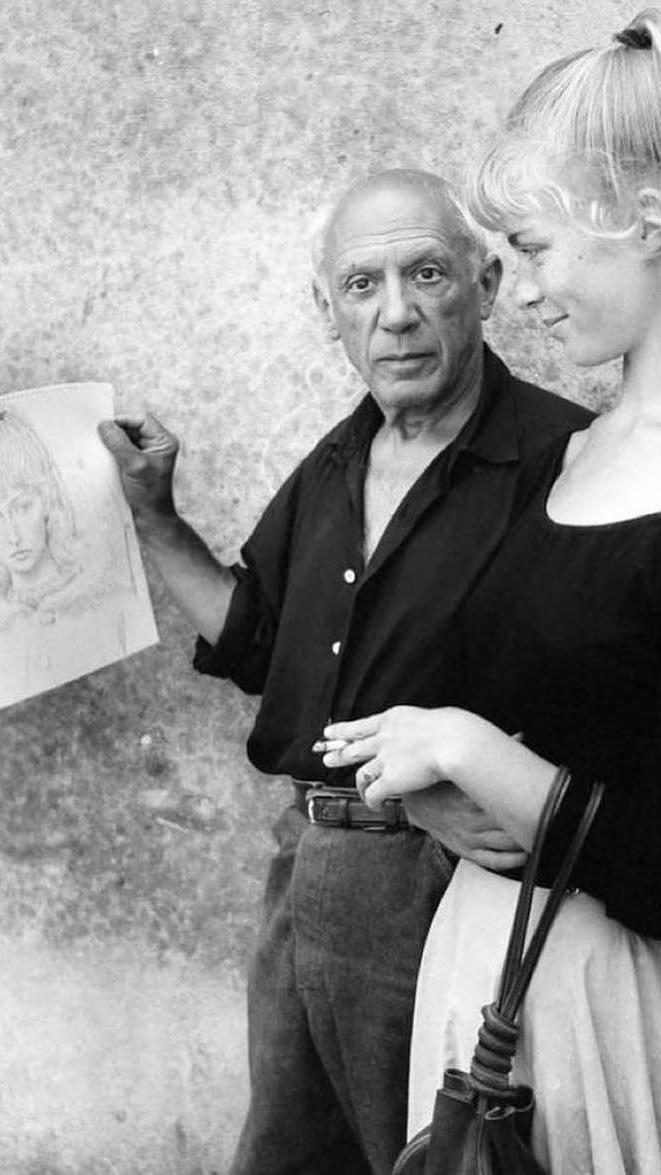

In this context, financial and career achievements replace aesthetic craft as an artistic endeavor’s primary goal. Nowhere is this transition clearer than in the shifting relationship between artists and the corporate world. ‘Selling Out’ has become ‘Getting The Bag.’ Cashing a check is the golden light at the end of the artistic tunnel for budding talent, who want their work in a corporate courtyard just like KAWS.

It’s not only the career that self-actualization funnels us towards, but the persona. Daily activity is subservient to a larger project of self-construction, which is increasingly mediated by the same platforms where we see our art. Creativity is instrumentalized to create not just art, but also a persona. In many cases, it is the persona that is used to market the work.

Let’s consider the Day Job again. At its best, a stable salary removes pressure from creativity. But self-actualization is an incessant taskmaster, a job you never clock out of. Outside pressure is reapplied by the persona. Reclaiming your space and time from a job or The Man is one thing. Reclaiming them from yourself is another.

Which brings us back to the degradation of free time. The truth is that many of us still do have some free time, but even if we did want to devote these hours to sincere aesthetic activity, by the time we reach them we’re burned out, dopamine poisoned, and have at our fingertips functionally infinite frictionless entertainment to consume.

So this is a pretty bleak picture. Now let’s inject the 40,000 people graduating with fine art studio degrees in the US every year. Not only are these graduates legion, they’re also broke (art degrees have the worst debt to earnings ratio of any diploma). Not only are they broke, they’re also mostly bad.

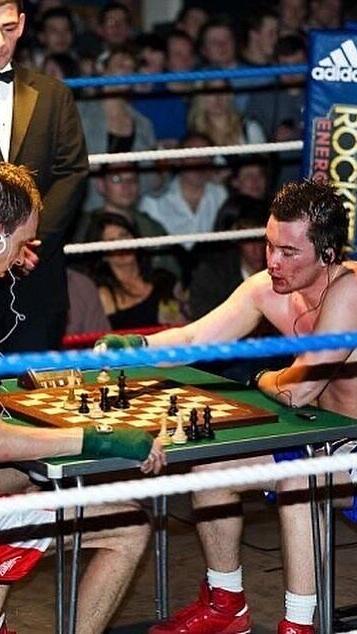

We’ve written a bit in the past about America’s cultural adoption of avant-garde European artists, teachers, and theorists during the second World War. One result was a shift in the art school model, away from craft oriented and highly prescriptive programs (which looked more like trade schools) towards a workshop model. Exploration, concept, and the ability to explain work to a group of peers was slowly prioritized over technical facility.

The result is a classic case of elite overproduction. The world is flooded with artspeaking BFAs. A few work their way into galleries and institutions, which is how this concept-first paradigm has come to dominate the open market too. But most don’t get that far. Which makes you wonder how these schools keep recruiting new crops of students, until you consider that their proposition aligns perfectly with the desires of a somewhat creative 18 year old seeking self-actualization and legible personhood.

Hopefully we’re starting to see the picture here. It’s a picture of art captured, perverted into a marketing device that sells degrees, a vocabulary that structures a professional ladder, a building block that promises a self.

And yeah, of course there’s AI. But those who are worried that AI might impact their success as an artist would do well to ask themselves whether they make good art in the first place. It seems that in general, across fields, AI will take your job only after society has made you bad at it.

This overwhelming negative picture (which also only just scratches the surface) is not supposed to be a blackpill, but a nudge towards a necessary reorientation of the way we think about the problems facing Art and The Artist, the solving of which might have less to do with banning new tools and more with rediscovering art as an aesthetic object, not a commercial one, and yourself as a soul, not a commodity.

AND ALSO, RELATEDLY

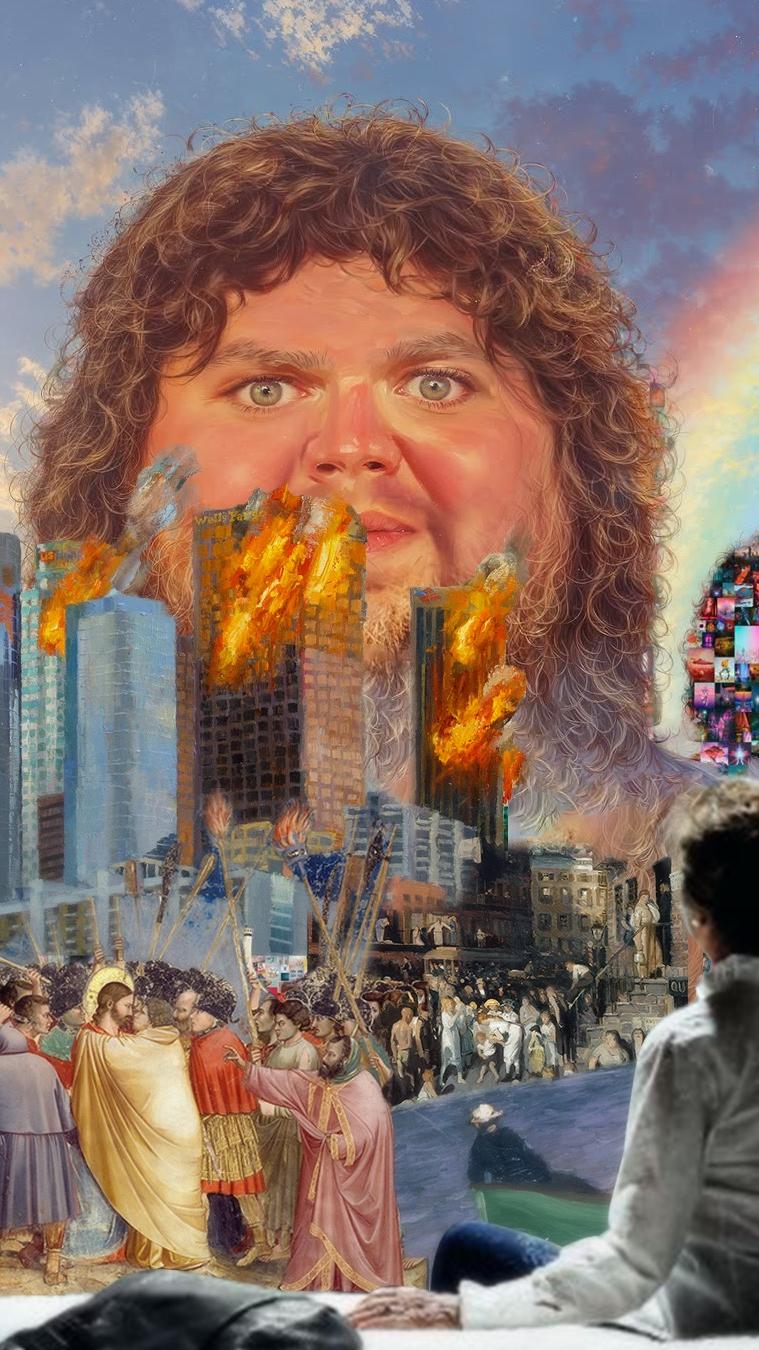

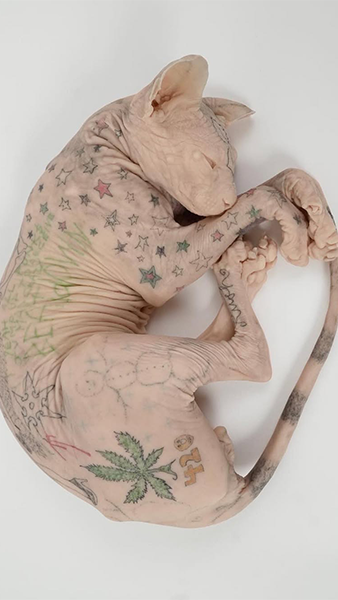

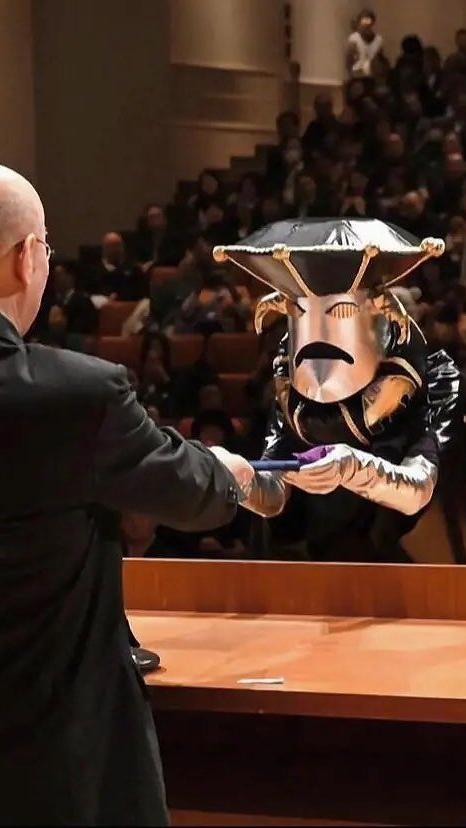

To complete this rosy portrait, a transmission from the Art World proper. Tim Blum, one of the gallerists who played a central role in establishing Los Angeles as an art hub, and helped bring artists like Takashi Murakami and Yoshimoto Nara into the spotlight, said of the the recent Art Basel art fair: “We didn’t have a single meaningful conversation Thursday through Sunday. It was profound.” Shortly after Basel, Blum announced he would be sunsetting his gallery.

![[object Object]](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/7hyzopih/production/531323f102cb8b365a10f5f98c83261b364dc3b5-1000x1250.jpg?auto=format&fit=max&q=75&w=500)

Nara's Miss Margaret (2016)

Written by Noah Jordan (@nnoahaonn)